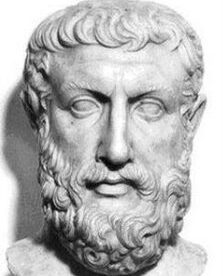

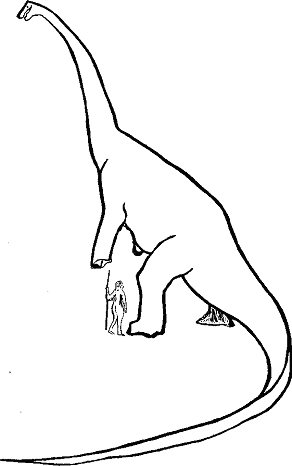

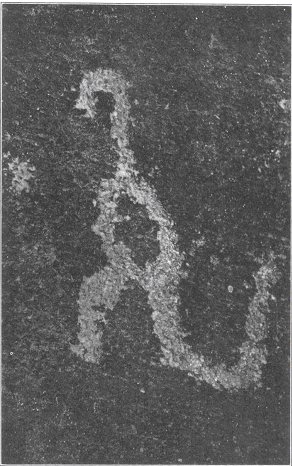

Photograph of Hava Supai Pictograph, followed by an illustration of Diplodocus. Both images were included in the publication of Discoveries Relating to Prehistoric Man.

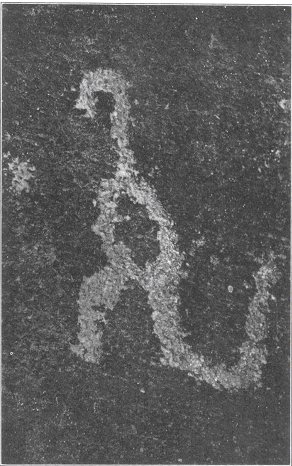

The fact that some prehistoric man made a pictograph of a dinosaur on the walls of this canyon upsets completely all of our theories regarding the antiquity of man. Facts are stubborn and immutable things. If theories do not square with the facts then the theories must change, the facts remain.

– Samuel Hubbard, Discoveries Relating to Prehistoric Man (5). As quoted in Cowboys & Saurians: Dinosaurs and Prehistoric Beasts as Seen by the Pioneers by John Lemay (339).

Located in remote and arid Northern Arizona near the oasis of Havasu Falls, this image and the canyon that bore it were discovered by a young Los Angeles prospector named E.L. Doheny and his party of several men, who were the first White men to visit this place. There were many hardships which comprised the original expedition; the most tragic of these was death of one of the party, a sailor named Mooney, who plummeted to his doom while trying to descend a waterfall which was posthumously named in his honor. Despite the risks involved with mounting an expedition to this place, several were undertaken before the much more conclusive 1924 expedition, which archaeologist Samuel Hubbard refers to in Discoveries Relating to Prehistoric Man, his aforementioned report:1

This canyon was first visited by the writer in November, 1894, and in February and March, 1895. Most of the matters of prehistoric interest described in this pamphlet, were observed at that time but their true significance was not fully recognized. Endeavors were made at various times to interest scientists in this discovery, but without avail.

Hubbard would once again visit the canyon in 1924 as the leader of the “Doheny Expedition”, which was sponsored by the prospector, now a major oil tycoon, who was drawn back to that place by the memory of those mysterious pictographs he had witnessed in his youth. Notably, a paleontologist was among the members of this expedition, alongside a sculptor and even a photographer, alongside two assistants and a guide. I list their names here as follows, for posterity’s sake:

- SAMUEL HUBBARD (Honorary Curator of Archaeology at the Oakland Museum)

- CHARLES W. GILMORE (Curator of Vertebrate Paleontology at the National Museum)

- ROBERT L CARSON (Photographer)

- JOSEPH F. ROOP (Sculptor)

- FRED V. SHAW & ARTHUR METSZER (Assistants)

- BUD CLAWSON (Guide and Packer)

What is especially unique and thoroughly sound about this case is, as a result of the presence of a photographer in this expedition, the researcher is not left to his own imagination as to what was witnessed. He can accurately assess these pictographs for what they are, not having to rely on a potentially unsuitable or unreliable description from a primary, or even tertiary source. Some may allege that these pictographs were a hoax. However, their incredibly remote location, the possibility of these paintings being “faked” is practically impossible. Who, especially at that time, would try to place a hoax that would (in all likelihood) not be found in the foreseeable future? The presence of academics well within the realm of the scientific establishment on site of this expedition should quell the opinions of the naysayers, the typical skeptics who question everything but their own skepticism. And for those of us who are inclined (understandably, I add) to doubt the scientific establishment, it speaks volumes that an archaeologist and a paleontologist would verify cave paintings which, by their mere existence, put into question their evolutionist and Lyellian biases.

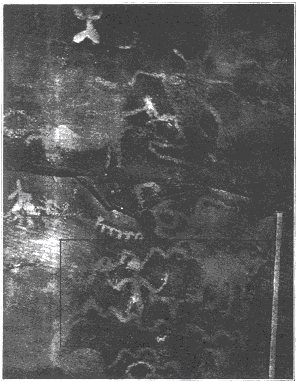

The dinosaurian illustration which composes the main subject of this article was not the only one of interest there, as Hubbard’s report about the expedition also includes information and images regarding pictographs of elephants and ibexes within the same cave. There were also other images, and even odd symbols found by the party, but record of these things survives to us only by this excerpt from the report:

On the same wall [as the dinosaur] were a number of other figures of goat-like creatures, serpents, and unknown forms. The most remarkable of these was a row of symbols, deeply incised, which resembled the Greek sign of Mars showing shield and spear, thus. The “desert varnish” had commenced to form in the cut, indicating an unbelievable antiquity.

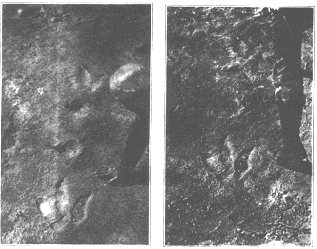

For reference, yours truly has organized the photographs of the other cave paintings below, with the same captions as written the original report.

First: Pictograph showing Elephant attacking large man. Second: Line drawing of Elephant figure made in Hava Supai, Canyon by Samuel Hubbard May 5th, 1923 (about 1/2 actual size)

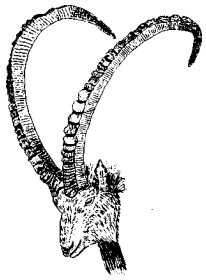

First: Detail from Ibex Panel in Lee Canyon. Ibex and Deer being driven into a trap or up a pass.

Second: Pictograph of Ibex showing one male and two females (located beneath Elephant and Dinosaur pictures).

Third: Head of Arabian Ibex, (capra Nubiana). These true goats, represented by several species, are found in the Pyrenees, in the Alps, the Carpathians; in Northern Africa, in Mesopotamia, in the Himalayas and in the Altai Mountains in Asia. They have never been known in America.

Hubbard posited that the elephants depicted in these cave illustrations depicted Imperial Elephants, which once lived in North America and were purportedly hunted down to extinction by the Indians a great many generations ago. Intriguingly, he writes in relation to this drawing and that of the dinosaur that:

There is no means by which we can tell whether the elephant was drawn before or after the dinosaur.

The dinosaur figure is cut into the sandstone much more deeply than the elephant. It was possible to make a good plaster cast of the dinosaur, but not possible to cast the elephant. Our surmise is that the two figures were made by different people and at different times and in a slightly different way. As stated before, the symbols near the dinosaur figure in which the “desert varnish” has formed in the cut, have a character all their own, and probably in point of time, precede all the others.

Hubbard’s definition of the curious term “desert varnish” not only helps clarify what he writes of here, but additionally broadens our knowledge concerning the origins of these pictographs:

The red sandstone contains a trace of iron. This iron, through the alchemy of unknown ages of time, forms a thin black scale on the surface of the stone, locally called the “Desert Varnish.” By taking any sharp point, such as a piece of flint, and cutting through this black surface, the red stone is revealed underneath, thus making a picture, without the use of pigment, which is practically imperishable. The only way one of these pictographs can disappear is to weather off. They show every sign of a great antiquity, and in the thirty years they have been known to the writer there is not the slightest change noticeable.

Though the ibexes are curiously out of place (there is no record of any species, living or extinct, having inhabited this continent), the apparently dinosaurian pictograph naturally elicits the most curiosity. Was it really a dinosaur, and if not, what could it have been?

?

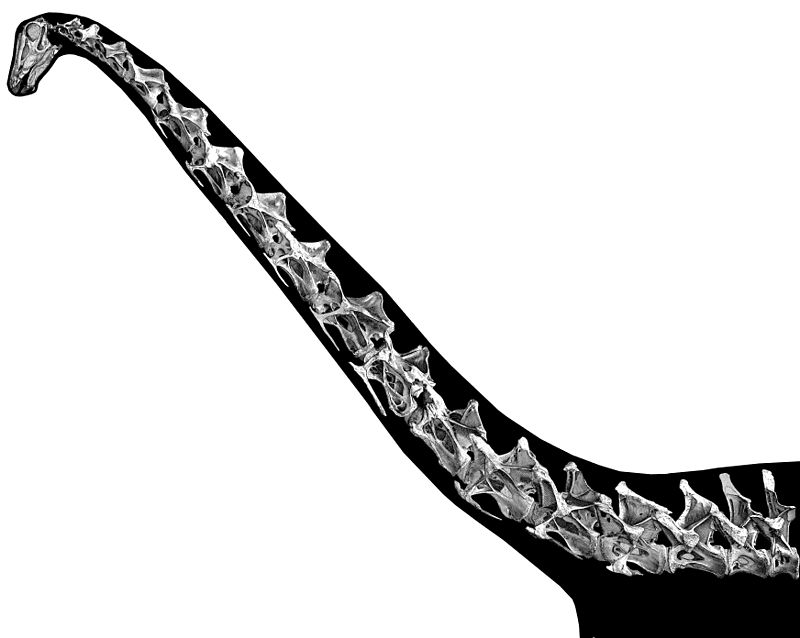

The specific species which Hubbard posited as the candidate for the creature represented in this pictograph is Diplodocus, a plant-eating sauropod that, according to the paleontologists of our time, lived during the so-called Late “Jurassic” era, an alleged 154-152 million years ago. Though the illustration of Diplodocus used by Hubbard to corroborate his thesis is considered outdated due to new information regarding the animal’s physiognomy, there is a striking resemblance between the pictograph and a modern depiction of this animal with its neck in an upright position:

Upright neck pose for D. carnegii based on Taylor et al. (2009) contrasted with Hava Supai pictograph.

Though it is a commonly held belief that this animal kept its neck in a horizontal position, an image which was popularized by how Diplodocus was depicted in the BBC Television series Walking with Dinosaurs, significant evidence stands against this opinion. In fact, a paper published in 2009 entitled Head and neck posture in sauropod dinosaurs inferred from extant animals (Taylor et al, 2009) proved, by means of corroboration with the skeletal structures of modern animals, that Diplodocus, along with other sauropods, held their necks upright.2 Since I do not wish to further extend this article by delving into the specifics, as fascinating as they are, I invite the reader to investigate this information for themselves. In particular I recommend this article which lays out the argument given in the original paper, but in a manner much more accessible to the average person.3

One might still claim that Diplodocus cannot be the animal depicted in the pictograph on the basis that the painting seems to show a bipedal creature, while this dinosaur was most assuredly a quadruped. Moreover, it seems to be dragging its tail, yet the modern reconstructions and the lack of any fossilized marks left by tail dragging have demonstrated that dinosaurs did not drag their tails.

To these objections, I propose the following solution. The animal was portrayed by the cave artist as a living creature, yet while it stood in a temporary bipedal stance, perhaps to reach a tree, much like the scenario which is presented in this depiction:

Illustration: Diplodocus Carnegii Family by Ken Kozoszka

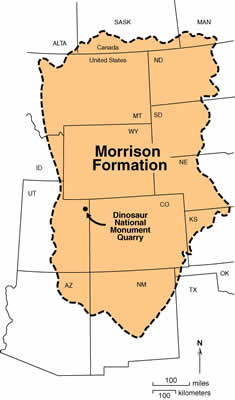

It is quite the coincidence that Diplodocus has been exclusively found in Morrison Formation, which encompasses a small part of Northern Arizona and that three of the most complete specimens of this species ever found were located in Carnegie Quarry (now Dinosaur National Monument) in neighboring Utah.4 Though these specimens most assuredly died during the Deluge (as this article argues),5 it is possible that perhaps a population of these creatures ventured back into this general region after the cataclysm’s end. The close proximity of Diplodocus remains to the location of this pictograph is too close to be dismissed out of hand.

Though Hubbard found no proof of Diplodocus ever having resided in the canyon, his team discovered a set of tracks left by a carnivorous dinosaur, which were, in his own words, “were not over 100 miles from the dinosaur picture.”

At the very least, this finding proved that dinosaurs had once been in the area, though it is uncertain if these visitors in particular had been around the same time as the people who painted the pictograph.

With all of these pieces having been put together, it stands to reason that the animal depicted in this cave painting was no fraud or forgery, but was a living, breathing Diplodocus. Of course, the acceptance of such a proposition, as noted by Hubbard himself in his report, leads to some very thought-provoking conclusions. If one continues to accept the millions of years myth, they may posit that man “developed” much earlier in the timeline, or that some dinosaurs survived into the so-called “age of mammals”. These possibilities, which in attempting to salvage the sacrosanct timeline of the scientific establishment raise more perplexing questions than sound answers, were stated by Hubbard himself:

If the reader agrees that this is a “dinosaur” then we are face to face with one of two conclusions. Either man goes back in Geologic time to the Triassic Period, which is millions of years beyond anything yet admitted, or else there were “left over” dinosaurs which came down into the age of mammals. Yet even this last conclusion indicates a vast antiquity.

Of course, the most obvious answer to this seemingly out of place pictograph, to the scientificist, is to dismiss it out of mere principle, as its very existence violates his false dogmas. Hubbard recorded an interaction which illustrates this intellectual obstinacy quite well:

About a year ago a photograph of the “dinosaur” was shown to a scientist of national repute, who was then specializing in dinosaurs. He said, “It is not a dinosaur, it is impossible, because we know that dinosaurs were extinct 12 million years before man appeared on earth.”

It is worth noting that the accepted date of the extinction of the dinosaurs was at that time 12 million years ago. Nearly a hundred years after this report, the accepted date has shifted to 65 million years.

But the hardest answer for modern man to accept in this regard, so it would seem (and one Hubbard refuses to consider in his report), is that the whole Old Earth hypothesis is spectacularly wrong, with all of its tenets – Uniformitarianism, Darwinism, radiocarbon dating, etc. – all of them absolutely false. This conclusion however, though not proved directly by this pictograph, is supported by its existence. It is only a hint of a much larger story, one that begins with that much derided – but ever sacred – book of Genesis.

FURTHER READING

More information about Havasu Canyon, Arizona: http://www.great-adventures.com/destinations/usa/arizona/havasu.html.

Library record of photographs taken on the Doheny Expedition: https://researchworks.oclc.org/archivegrid/collection/data/1019732018.

- “Doheny Expedition.” Creationism.org.

- Taylor, Michael P., et al. “Head and neck posture in sauropod dinosaurs inferred from extant animals.” ACTA PALAEONTOLOGICA POLONICA, 2009. www.app.pan.pl/archive/published/app54/app54-213.pdf.

- Taylor, Michael P. “Sauropods held their necks erect.” 2 Mar. 2011. www.miketaylor.org.uk/dino/neck-posture/#gsc.tab=0.

- “Diplodocus longus.” NPS. www.nps.gov/dino/learn/nature/diplodocus-longus.htm.

- Hoesch, William A., and Steven A. Austin. “Dinosaur National Monument: Jurassic Park Or Jurassic Jumble?” ICR, 1 Apr. 2004. www.icr.org/article/dinosaur-national-monument-park-or-jurassic-jumble/.