Available from Amazon. You can read this book for free on Archive.org!

Book Length: 346 pages

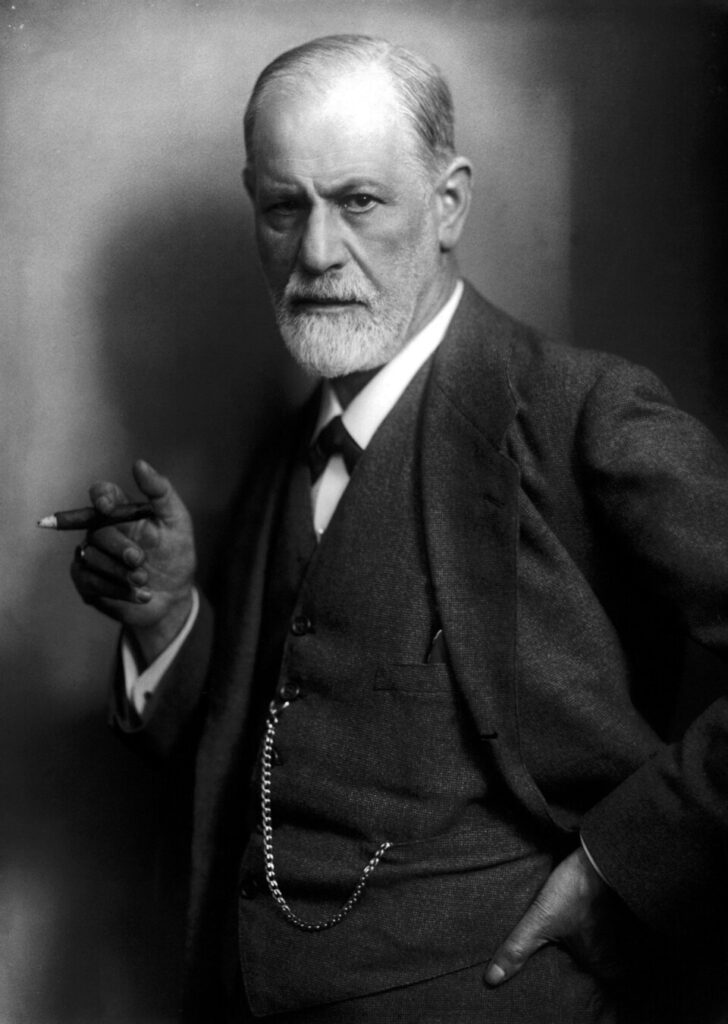

Undoubtedly, the thought of Sigmund Freud has had not only an extensive influence in scientific quarters, but also a colossal impact in popular culture. His ideas about sexuality have made him, in the eyes of the world, a “great mind”—but where did those ideas come from? While Freud is commonly portrayed as an original thinker, Dr. David Bakan presents quite a different view in his eye-opening book Sigmund Freud and the Jewish Mystical Tradition. In contrast to the prevalent view, in which Freud’s Jewish identity is either unmentioned or downplayed, Bakan argues that it laid down the foundation for his anthropological and cultural claims.

Summarizing this argument in a sentence in the beginning of this work, Bakan states that “Freud, consciously or unconsciously, secularized Jewish mysticism; and psychoanalysis can intelligently be viewed as such a secularization” (25).1 To add a further nuance to this point, though Freud borrowed from Jewish religious beliefs, according to this author his association with Judaism became more racial and cultural in his adulthood. For in the last chapter, he writes of Freud that “His identification was rather with Jews as a people and as a continuous historical line” (315). Bakan, who was himself Jewish, succeeds in proving this case, as any survey of these pages will demonstrate that he is well-versed in both Freudianism and the Jewish religion and culture after the coming of Christ. For instance, he raises this intriguing point while discussing the oral tradition of the Kabbala:

(35-36)

The Kabbalistic tradition itself has secrecy as part of its nature and deals with secret matters. The Kabbalistic tradition has it that the secret teachings are transmitted orally to one person at a time, and even then only to select minds and by hints. This is indeed what Freud was doing in the actual practice of psychoanalysis, and this aspect of the Kabbalistic tradition is still maintained in the education of the modern psychoanalyst. He must receive the training orally (in the training analysis). As the modern practicing psychoanalyst is quick to tell anyone, psychoanalysis is not to be learned from books!

It would therefore be well to further examine the course of Bakan’s argument in some detail, as, given the prevalence of Freud’s thought to this day, understanding the process of this “secularization” of the false tradition of the Pharisees will bolster our efforts in combating the mass sexualization of culture that Freud inaugurated.

If Freud truly secularized Jewish mystical thought, then his role as an “objective” observer of the inner workings of the human mind must be reevaluated. For if these beliefs influenced his findings, they must have influenced the view he had of himself; this is precisely what Bakan uncovers. For according to him, Freud developed a messianic impulse which intimately involved itself in his lifelong fascination with the figure of Moses, which consequently came to shape the very purpose of psychoanalysis. In a weighty analysis of Freud’s early essay “The Moses of Michelangelo”, Bakan lucidly comments:

(127)

If Freud conceives of himself as the new Lawgiver, then the new Lawgiver must at one and the same time be like unto Moses, the previous Lawgiver, whose place he must preempt, and must be destructive of Moses. The new Lawgiver must revoke the older Law. The identification with Moses turns into its opposite, the destruction of Moses.

Freud saw himself as a successor to Moses, but also one who, in Bakan’s words, “must be destructive of Moses.” Such a juxtaposition is not unlike the earlier Jewish false messiahs Sabbatai Zevi and Jacob Frank—and this is something quite apparent to Bakan, who provides the reader with brief histories of these men and compares them and their messages to the character of Freud and his message of psychoanalysis. In a more broad comparison of the conventional themes of Jewish Messianism and Freud’s own work, Bakan remarks that:

One of the critical features of Messianism is its goal of leading people out of slavery and oppression. Thus Freud’s whole effort at the creation of psychoanalysis may be viewed as Messianic in this respect. The aim of psychoanalytic thought is the production of greater freedom for the individual, releasing him from the tyranny of the unconscious, which is, in Freud’s view, the result of social oppression.

That psychoanalysis should have grown up in the context of the healing of the sick who were incurable by orthodox medical means accords with the Messianic quality of the psychoanalytical movement. For Messianism characteristically proves itself first by miraculously healing the sick. Thereafter it reaches out to large-scale social reform. So Freud’s psychoanalysis reached out from the healing of individuals to the healing of society.

(170)

Thus Freud’s seemingly secular quest for the healing of individuals from their neuroses becomes a sort of divine mission; like Moses, in this view Freud has been “anointed” to free others from spiritual and physical slavery. His claim of healing the mentally ill by his method is transformed from a mere debate of medical science to a proof of the “revelation” he has received. But unlike Christ, who was truly the “anointed one”, Freud’s alleged cures are unimpressive and doubtful in their results; they are the quackery of a prideful Jew who sought to hypocritically honor Moses by undoing the Law. Compare this to Jesus Christ, who deceived none and publicly healed the sick; who said that He “came not to destroy, but to fulfill” (Matthew 5:17) that ancient Law which was the figure of the New Testament yet perverted by the Pharisees, who taught “doctrines and commandments of men” (Matthew 15:9). While Christ has showed and continues to show the way to true freedom through self-denial in obedience to the Father, Freud has ruined the happiness of millions through his approval of lust in the name of “liberating” mankind from “repression”.

Though his false gospel of sexual liberation is commonly criticized as the product of a warped mind, the root of this warping is not discussed—and that root is the Kabbala. Detailing the attitude of this tradition towards sexuality, Bakan notes:

(272)

Never in the Jewish tradition was sexual asceticism made a religious value. The commandment to be fruitful and multiply was always taken extremely seriously in both rabbinical and mystical traditions. In contrast with other ascetic forms of mysticism, the Jewish mystics ascribed sexuality to God himself. The Jewish Kabbalist saw in sexual relations between a man and his wife a symbolic fulfillment of the relationship between God and the Shekinah.

In Judaism, therefore, the marital act is divinized following from the rabbinical and mystical misinterpretation of Genesis. One may rightly contend with Bakan’s statement that celibacy was “never” sacred in the “Jewish tradition”; though it is incorrect of Old Testament Judaism (for the Prophet Elias and the ancient Carmelites stand as witnesses to the contrary), it is true of Pharisaical and Talmudic Judaism.

Following from the rejection of celibacy and the absurdly blasphemous sexualization of God Himself, the theology of Judaism after Christ shows itself to be inherently carnal. And because they are carnal, they are inward in their thinking, lacking a true sense of the transcendent and the spiritual. For as St. Paul illustrated, celibacy practiced according to the way of Christ (who was Himself celibate) makes a man more spiritual and not less so:

(1 Corinthians 7:32-33)

He that is without a wife, is solicitous for the things that belong to the Lord, how he may please God. But he that is with a wife, is solicitous for the things of the world, how he may please his wife: and he is divided.

But because the Jews rejected Christ, they reject this wisdom. Thus, the eyes of their minds are bent towards the things of this world instead of what is above in Heaven.

Freud was raised according to this mentality, and his whole attitude towards sexuality demonstrates it. Bakan, stating the importance of sexuality in Freud’s anthropology, writes that:

(273)

For in Freud, sexuality is not the simple act of copulation, but is rather a complex metaphor in which all human meanings are somehow involved.

Just as how in the Kabbalistic tradition sexual relations between a husband and wife are a “symbolic fulfillment” of the sexualized relationship of the male Jewish God and his female essence, the Shekinah, so too in Freud’s view sexuality is a “complex metaphor in which all human meanings are somehow involved.” In both perspectives, sexuality is not simply a part of human life—it is assigned an absolute value, thus taking on the aspect of a sacred mystery around which all others revolve.

These ideas are of course quite different to the perspective of Catholic tradition, which ultimately sees sexuality as an important element in God’s plan to bring souls to their proper end or purpose, which is the vision of Him in Heaven. Sexual relations between husband and wife are indeed sanctified by the sacrament of matrimony, but the symbolism of this relationship is one that is ordered to the sacrifice of the celibate Christ for His Church. In Catholicism, therefore, the first end of marriage is the procreation of children with the added duty of forming the child in Christian virtue; the unity of the spouses, on the other hand, is the second end. This ordering shows that, in the Faith, the more carnal aspect of sexuality is subordinated to a higher spiritual goal.2 In Judaism, as has been noted, there is nothing equivalent.

Freud’s obsession with sexuality as the supreme mystery of human existence can hardly be mentioned without reference to his infamous (and thankfully often derided) views on incest. As with his views on sexuality in general, his views on incest also must be placed in the context of Jewish culture and religious tradition. Concerning this vital background information, Bakan tells us that:

The Jews, because of their endogamy, characteristically had an incest problem, and part of the role of Jewish mysticism was to provide devices for coping with the intense feelings of guilt associated with incest wishes.

(292)

Connecting this point to Freud’s interest in and interpretation of Oedipus Rex, Bakan comments on the relevance of this famous aspect of his life to the incest problem within the Jewish community:

(293)

In the classical Oedipus story, it will be recalled, incest takes place as a result of a freak event which separated the partners so that they did not recognize each other as adults. The major reason for the customary arrangement of marriages by the elders of the Jewish community may very well be that the elders were the bearers of essential information concerning consanguinity.

With this frame of reference, Freud’s view that incest wishes are to be found buried deep within the recesses of the “subconscious” among all men can, consequently, be reasonably viewed as the projection of a characteristically Jewish problem onto Gentile humanity. As the potentially embarrassing implications of this conclusion would be considered unpleasant and even “antisemitic”, the likely reaction of the Jewish community towards those outside their fold highlighting these connections accounts for the silence of mainstream academia on this matter.

This book therefore is an excellent resource in understanding the real Freud—a man driven by a messiah complex who proselytized a Judaized anthropology in the language of secular science. A Catholic reader ought to keep in mind that, given the differing perspective of Bakan to that of the Faith, the author will inevitably present errors as truths and that therefore one should be on guard when reading him.

-

All quotations of this text are provided from:

Bakan, David. Sigmund Freud and the Jewish Mystical Tradition. Van Nostrand. 1958.

-

See for reference:

Plese, Matthew. “On the Purpose of Marriage and the Impossibility of Divorce.” Fatima Center. 29 Nov. 2019.