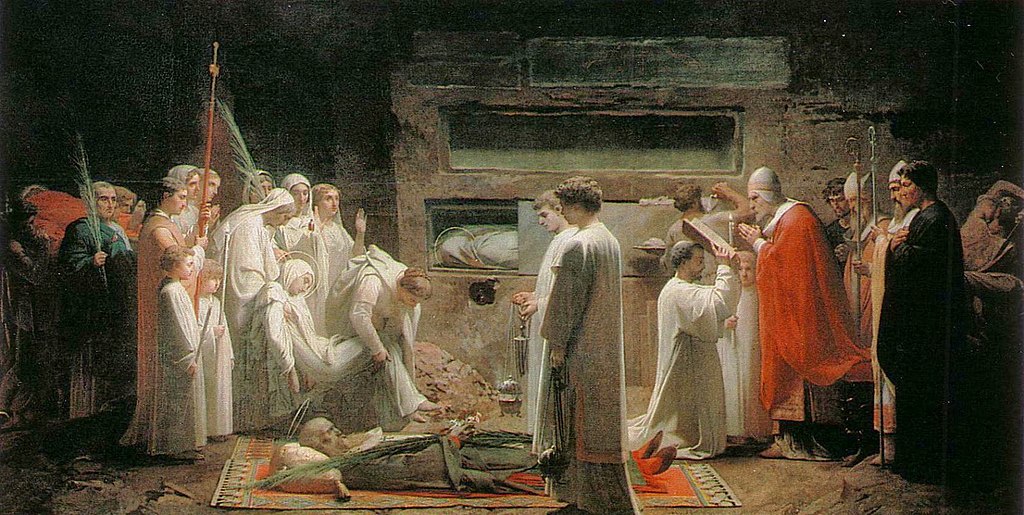

The Martyrs in the Catacombs by Jules-Eugène Lenepveu

Available from Thriftbooks and Amazon

Book Length: 274 pages

Ours is a time in which basic truths must be rediscovered, owing to a long process of spiritual, intellectual, and cultural decline in the West. Concepts which can be plainly known through the light of reason such as the necessity of the family, the organic development of society, the differences among the races, and the nature of manhood and womanhood have been absurdly misrepresented and dragged through the mire in the names of “intellectual freedom” and “progress”. Such a state of affairs results from a civilization that has been hijacked and betrayed from within; its institutions proudly shun reason and include all errors in their pantheon to the exclusion of the one truth that comes from the Faith. The authors of this decline have promised a heaven on earth, but in reality they have made it a hell. Nowhere is this better seen than in Europe, where the native populace of these great nations are subject to governments who have abused morality to legalize the mass invasion of peoples and lifestyles utterly foreign to Europe and her civilization. These same governments demoralize their people much in the same manner as Americans are demoralized by theirs on the other side of the Atlantic; but there it is all the more troubling, for Europe is the heart of Christendom—in comparison, America merely remains an outer limb of that sublime body.

The basic, yet vital question that confronts us is this one: what is Europe? We are, however, not the first to face this matter—for the eminent Catholic historian Christopher Dawson masterfully addressed it directly in his 1932 work The Making of Europe, a book which is even more relevant to us today than at the time he was writing.

Countering both the viewpoint of an internationalism that seeks to flatten the achievements of European civilization in order to integrate it into a pretended global civilization and concepts of European nationhood that were too inward looking, Dawson articulated the sensible idea—and one which is in accord with historical reality—of Europe as a community of nations. This community, however, is not to be understood as a political state or even a political federation (as the Holy Roman Empire was, or its dupe the European Union is today), but instead as a real communion that transcends flags and borders while not denying their value; that sees these peoples—Italians, Germans, Englishmen, Frenchmen, Spaniards, Dutchmen, Greeks, Celts, etc.—as parts of the whole that Dawson terms “the European unity”. Explaining this matter, he aptly writes:1

The ultimate foundation of our culture is not the national state, but the European unity. It is true that this unity has not hitherto achieved political form, and perhaps it may never do so; but for all that it is a real society, not an intellectual abstraction, and it is only through their communion in that society that the different national cultures have attained their actual form.

(20-21)

Thus in composing this work, Dawson wished to explore the nature of this unity and the significance it has for modern times. In a grand tour of European history, the author traces the origin of this unity in the Roman Empire and uncovers how it was forever changed and marvelously enriched by the coming of Christ and the establishment of His Church. This, however, is not an entire history of Europe from the Empire to the twentieth century; for his intention was to convey the development of the European unity from Antiquity to the end of the Age of the Vikings. Though Western Europe takes up much of the scope of this work, the rich history of the Byzantine Empire does not escape his grasp—and thankfully he approaches this subject with appreciation and respect, qualities which are unfortunately often lacking in historians who treat of that thousand year empire. He also takes time to delve into some Middle Eastern history in some of these chapters, but this detour is not in the least bit jarring, since the author skillfully interweaves them into his overarching narrative; for without giving some attention to the rise of Mohammedanism, how could one truly grasp the threat it posed (and indeed still does pose!) to Europe? But in the vast span of time he covers, Dawson immerses the reader in the atmosphere of long-gone centuries—and his style is only aided by his thoughtful selection of primary sources and inclusion of helpful footnotes.

The author is not satisfied to merely relate a narrative of history—as many textbooks are prone to doing—for here one finds a brilliant mind at work, as Dawson was a man whose vision of the past was not tainted by unhealthy bouts of idealism or cynicism. For instance, in the Introduction one finds a lucid description of the mentality of the Middle Ages:

(18)

If that age was an age of faith, it was not merely on account of its external religious profession; still less does it mean that the men of that age were more moral or more humane or more just in their social and economic relations than the men of to-day. It is rather that they had no faith in themselves or in the possibilities of human effort, but put their trust in something more than civilisation and something outside history…The foundations of Europe were laid in fear and weakness and suffering—in such suffering as we can hardly conceive to-day, even after the disasters of the last eighteen years. And yet the sense of despair and unlimited impotence and abandonment that the disasters of the time provoked was not inconsistent with a spirit of courage and self-devotion which inspired men to heroic effort and superhuman activity.

Such a view illustrates a realistic perception of the times, yet including—and not excluding, as many authors sadly do today—the transcendent and deeply Catholic worldview of the Age of Faith which only seems alien to many of the faithful in our times because our Dark Age has been formed by the decadence of secularism. More than this, the Modernists among the clergy have deliberately attempted to forever sever the sons and daughters of Christendom from her uplifting dignity by shaking hands with the Pontius Pilates and Caiaphases of the twenty-first century. Instead of converting secular society to that vision of society which alone can save it, they have been converted by cultural freemasonry and give only a token resistance to the consequent force of bourgeois materialism: and because negation cannot beget, this plague ends in nihilism. No wonder then the prevailing despair of our times, especially in the lands of Europe! For her peoples are largely divorced from this “something more” than civilization and “something outside” history. Thus they are stuck appealing to mere rights and laws written by conniving internationalists, mere relative clauses, rather than those rights and laws which are founded upon the eternal laws of God, who alone is perfect Justice. May they then return to Him alone who can save them through the help of His holy priests, Him alone who can lift them above despair to the heroic courage and self-sacrifice of a Roland or a St. Genevieve!

But as the new Europe will have to be reborn through this higher faith in the midst of great suffering, so too was the old Europe born out of the dark age that followed the collapse of the Carolingian Empire. On how this transformation immutably affected Europe for the better, Dawson comments that:

(230)

…[O]ut of the darkness and confusion of the tenth century the new peoples of Christian Europe were born. The achievements of the Carolingian culture were not altogether lost. Their tradition remained and was capable of being applied anew to the circumstances of the regional and national societies wherever there was any constructive force that could make use of them. Above all, the forces of order found a rallying-point and a principle of leadership in the Carolingian ideal of Christian royalty. The kingship was the one institution that was common to the two societies and embodied the traditions of both cultures. For while the king was the lineal successor of the tribal chieftain and the war leader of the feudal society, he also inherited the Carolingian tradition of theocratic monarchy and possessed a quasi-sacramental character owing to the sacred rites of coronation and anointment. He was the natural ally of the Church, and found in the bishops and the monasteries the chief foundations of his power.

It was then the precedent set by that alliance of Church and State practiced by Charlemagne and his successors that brought Europe out of the Dark Ages, and made possible the flourishing of her culture. For without the sacramentalization of their monarchical principle and the duties before the Church it required of them, would not the princes, dukes, and kings of Europe have degraded themselves into a less cultured version of the “enlightened despots” of the eighteenth century? The false narratives of history which disgustingly paint this order as the bane of civilization therefore must not only be considered anti-Christian, but also anti-European; for though the culture of the Roman Empire was indeed admirable, nothing surpasses the achievements of the Medieval European civilization.

When one considers the achievements of the former, naturally the brilliant illuminations of the Irish monks, the great Gothic cathedrals, and the works of the Flemish Masters come to mind. But those achievements would not have been possible without the conversion of the Northern European peoples to the Faith, which consequently must stand as a higher achievement. Reflecting on the pivotal role that was played by the states that arose in Northern France, Normandy, Flanders, and the Rhineland in this respect, Dawson opines:

(241)

It was this middle territory, reaching from the Loire to the Rhine, that was the true homeland of mediaeval culture and the source of its creative and characteristic achievements. It was the cradle of Gothic architecture, of the great mediaeval schools, of the movement of monastic and ecclesiastical reform and of the crusading ideal. It was the centre of the typical development of the feudal state, of the North European communal movement and of the institution of knighthood. It was here that a complete synthesis was finally achieved between the Germanic North and the spiritual order of the Church and the traditions of the Latin culture. The age of the Crusades saw the appearance of a new ethical and religious ideal which represents the translation into Christian forms of the old heroic ideal of the Nordic warrior culture.

Thus the Church did what the legions of Augustus could not: integrate the peoples beyond the Rhine into the European unity. And this she did largely without the use of the sword, but primarily through the deeds of holy monks and missionaries like St. Boniface—a process which is given ample treatment by the author in the eleventh chapter of this work. In fact, Dawson’s coverage of the conversion of the Northern Europeans thoroughly dismantles the foolish accusations that the clergy were content to leave the peasantry in ignorance about the Christian religion. He is concise and excellent there, as is the consistent theme of his study, in illustrating the successful transformation of the civilized world of the Roman Empire and the scattered European barbarian tribes into the whole of European Christendom. Across the pages, this historian is keen to convey to the reader the reality of this through his recourse to the sources; one particularly striking example comes in the last chapter, in which he provides a masterful yet brief analysis of how The Song of Roland is a product of this true enlightenment. He writes:

(Ibid)

In The Song of Roland we find the same motives that inspired the old heathen epic—the loyalty of a warrior to his lord, the delight of war for its own sake, above all the glorification of honorable defeat. But all this is now subordinated to the service of Christendom and brought into relation with Christian ideas. Roland’s obstinate refusal to sound his horn is entirely in the tradition of the old poetry, but in the death scene the defiant fatalism of the old heroes, such as Hogni and Hamdis, has been replaced by the Christian attitude of submission and repentance.

This Christian epic encapsulates the hope of the Catholic religion in the face of defeat; for unlike the false gods, Christ rose from the dead. It is understandable the “same motives” of the ancient epics find their place in this legend of Charlemagne’s greatest knight, but as Dawson indicates these accidents of the old Hellenistic and Norse cultures are not destroyed but are purified in relation to the truths of the Faith. For as the popular saying goes, grace does not destroy nature—it builds upon it. Europe today has alienated herself from both the heroic fatalism of her pagan ancients and the spirit of martyrdom of her Christian forefathers in favor of the poisons of atheistic materialism and humanistic moralism, whose only heroes are those who, like the prisoners of Plato’s cave, honor themselves according to an illusory existence.

But from such a glorious rise, how then did the decline of the European unity begin? Dawson, with a look back at the end of this journey and a look to what laid ahead for Europe, identifies the Protestant Revolution as the starting point. He explains:

(243)

In spite of religious disunion, Europe retained its cultural unity, but this was now based on a common intellectual tradition and a common allegiance to the classical tradition rather than on a common faith. The Latin grammar took the place of the Latin Liturgy as the bond of intellectual unity, and the scholar and the gentleman took the place of the monk and the knight as representative figures of Western culture. The four centuries of Nordic Catholicism and oriental influence were followed by four centuries of Humanism and occidental autonomy.

But this new phase of the European civilization was not built to last, for it stood on weaker grounding than what came before it. For this was a unity founded merely on culture, not on faith and culture—and even the great classical tradition could not prevent the inevitable slide into materialism without a sound spiritual backing. Without the monk to instruct the nations of Europe in not only the language of the Universal Church but also the virtues of the Christian religion, and without the knight to uphold the chivalric code which was founded upon the basis of those same virtues, many of these European gentlemen and scholars would inevitably find themselves confused and adrift in matters of religion. And because theology is the queen of the sciences, their mistakes in this realm would trouble the other fields of study and end in perversions of morality in the world outside of the schools and salons. Thus reflecting on the aftermath of those four centuries of “Humanism and occidental autonomy” in his time, Dawson comments:

(Ibid)

To-day Europe is faced with the breakdown of the secular and the aristocratic culture on which the second phase of its unity was based…We can no longer be satisfied with an aristocratic civilisation that finds its unity in external and superficial things and ignores the deeper needs of man’s spiritual nature.

If Europe was “faced” with this “breakdown” in the nineteen-thirties, then over the past seventy years she has only descended further into the abyss. Only a return to the Faith that built Europe can answer the spiritual needs of Europeans, and indeed the spiritual needs of the other races of mankind that even today look to that benighted continent for guidance.

This work is therefore a superb historical text, and should be read by all Catholics who are interested in matters of history—especially those who wish to learn about the role of our Faith in European culture and the origins of Christendom. Do not allow the fact that this text was written by a true academic to dissuade you: for although Dawson never “talks down” to the reader, neither is he inaccessibly erudite in his use of language. He has shown us the road to the great past of Europe, and in giving us the inspiring story of her emergence from near destruction to a renewed vigor, has shown us the road upon which—if she is to survive—she will need to return to in the future.