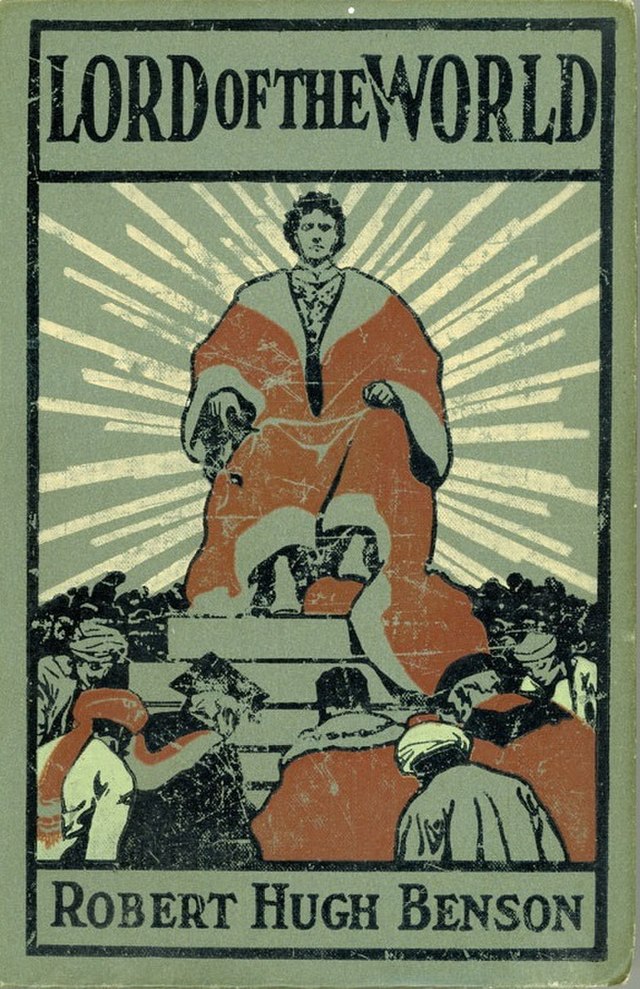

Original book cover of the Lord of the World by Robert Hugh Benson

Available from TAN Books and Angelus Press. You can read this book for free on Archive.org!

Book Length: 368 pages

Over a decade ago there was a burst of enthusiasm for the dystopian genre of fiction; it was a fire that shot out, and then was consumed by itself. Though some of these entries have poignant criticisms about the state of modern society, none ever reached the profundity of a much earlier entry in this genre—Msgr. Robert Hugh Benson’s Lord of the World. Despite it having been published in 1907, the dark vision of the world which Benson invites us to consider has more to say—and will have more to say to generations still to come—than the messages of The Hunger Games or The Maze Runner. Therefore, while avoiding the unnecessary revelation of major plot points, important aspects of this novel will be here examined.

The ominous march of the shadowy Julian Felsenburgh from a rumored peacemaker to the Antichrist of the Book of the Apocalypse is masterfully executed. Since the reader obtains only a gradual knowledge of this seemingly otherworldly personality from Benson’s cast of characters and found texts within these pages, the suspense around him runs throughout the narrative. The reader is quite simply tempted to always be anxious for what Felsenburgh will do next, as both the secular masses and the Catholic remnant of this world are. One thus discovers Felsenburgh alongside the characters, adding to the immersion of this alternative history of the twenty-first century. And this alternate twenty-first century is nightmarish—in some regards it resembles our own bleak present, but in other ways it does not.

Notably, Benson’s 2007 is a world drowned in secularism and unbelief—as was our own 2007, and our world as it has “progressed” since then.1 There are other points of connection, such as the prevalence of air travel and the legalization and widespread acceptance of euthanasia. Both were ambitious claims to make about the future in the early twentieth century. Yet even with this prescience in this regard, he—and indeed no man of his time—could have predicted the digital world and the banes it would unleash upon mankind.

The draconian nature of Felsenburgh and his humanist cult bear some resemblance to the Liberal-Marxism of the present. There is, however, a major difference between the two: while Felsenburgh’s system is coldly masculine in its rejection of God and the exaltation of Man, Liberal-Marxism is wildly feminine in its emotional moralism, though they both aim for the same ends. Only compare the rhetoric of Felsenburgh and his followers in this novel to the average leftist and the professional idiot class of the universities in the real world to see this divergence. The religion of this “lord of the world” then shows us an alternate route which was conceivable for the enemies of God to take in Benson’s time, but is unlikely in our own. Delving into this matter further, once one understands that the logic of Felsenburgh is rooted in Hegelianism, the reader can better realizes the vacuity of his humanism, which—much like our present humanism—slaughters man in the name of man. In tandem with this, by understanding this philosophical grounding the reader will also truly grasp the parallelism which Benson has integrated into his story between Felsenburgh and the hero of the story, Father Percy Franklin.

The identical appearances of these two men is a point that is stressed throughout the novel. One character even remarks that this seeming coincidence is “A kind of antithesis—a reverse of the medal” (196).2 “Antithesis” is the keyword here; it points to a relationship between Felsenburgh and Father Franklin that is akin to the relationship of thesis and antithesis in the famous Hegelian dialectic. Demystifying this process, the learned Thomist philosopher Étienne Gilson remarks that:3

(Gilson 250)

The progressive actualization of the world-leading Idea entails the submission of individuals to the unity of the State. The ideal State itself is progressively working out its unity through the necessary opposition between particular states. The State, then, in Hegel’s own words: “is the march of God through the world,” and there again the path of God is strewn with ruins.

The State then resolves the “necessary opposition” of thesis and antithesis through the creation of a synthesis that will combine elements of both the former and the latter. The thesis and antithesis, however, are not left the same; the Hegelian system in fact demands their liquidation by means of demanding an absolute and unhesitating submission to the new unity in order to bring about peace. Without further comment, it will suffice the reader to know that this is precisely the trajectory of Felsenburgh’s grand strategy. In this light, Father Franklin has been providentially chosen to act as God’s counter of the seemingly “outdated” thesis of Catholicism to the antithesis of international Marxism. As Felsenburgh acts as the incarnation of the Hegelian Idea, which is but the “ghost of God”, Father Franklin is divinely chosen by the Holy Ghost to spearhead the last struggle against the “man of sin” (2 Thessalonians 2:3).

Sensing the importance of this unassuming priest, the Pope invites him to Rome and grants him an audience. In their discussion, which inevitably pivots to the question of how best to combat the growing apostasy of the nations, Father Franklin gives the following answer:

Holy Father—the Mass, prayer, and the rosary. These first and last. The world denies their power: it is on their power that Christians must throw all their weight. All things in Jesus Christ—in Jesus Christ, first and last. Nothing else can avail. He must do all, for we can do nothing.

(128)

Indeed—the Mass, prayer, and the rosary! Not only is this recourse to the finest spiritual armaments of the Church sound in the context of this novel, but it is also an apt consideration for our age. Whether the reality of the twenty-first century is as grim as this novel’s version of it, the fundamental truth remains that by making these three the focus of our lives we are putting Jesus Christ “first and last”. The world “denies their power” because they deny His power; but by cooperating with His power through these gifts, we allow Him to transform ourselves into the brave souls we are meant to be.

Though Benson did not foresee the ongoing Crisis in the Church, we must keep in mind that his presentation of an unquestionably zealous pontiff and a thoroughly orthodox Catholic hierarchy who stand firm against the forces of darkness should not be as alien an idea to the faithful as it unfortunately seems to us. Yet we must not despair; the same Papal throne that has been so polluted by heresy also has seen the filth of the pornocracy and the scandal of Avignon, and was almost forever torn in three by the Great Western Schism. It survived these crises as it will survive the present crisis, by the promise of Christ and the power of the Holy Ghost.

And the idea which I am attempting to communicate here is quite in line with one of the most moving themes of this work—that the light can be found even in the darkest of places and in the darkest of hours. For the author is an excellent portrait-painter of the interior life; one would be hard pressed to find a better depiction of it in fiction, for through some otherworldly scenes with Father Franklin the reader catches a delightful glimmer of how a soul converses with God.

In closing, this work is recommended to all Catholics. This is a sublime work, full of thought-provoking considerations and consolations, not only for our benighted age—but for all time.

-

As the book takes place about a hundred years after its publication, the events we witness within the plot must take place around 2007. -

All the quotations of this text are provided from:

Benson, Msgr. Robert Hugh. The Lord of the Word. TAN Books. 2016.

-

Gilson, Étienne. The Unity of Philosophical Experience. Sheed and Ward. p. 250.