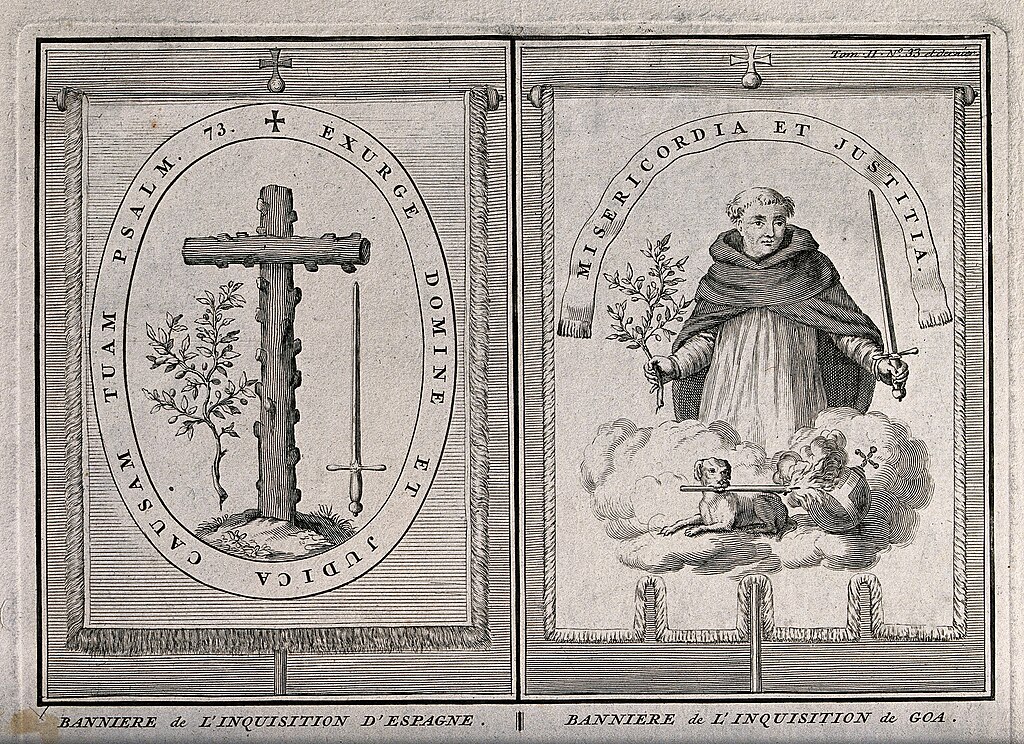

Left, the banner of the Spanish Inquisition; right, banner of the Goa Inquisition by the Portuguese.

Available from Abebooks, Amazon, and Thriftbooks

Book Length: 384 pages

Presently, the study of history is riddled with distortions. Of these, one of the most enduring negative myths in historiography is that of the dreadful Inquisition. Undoubtedly, the spellbinding influence of this myth has warped—and continues to warp—the minds of untold millions to the detriment of their souls. For despite the remarkable efforts of scholars in the past thirty years to dismantle it, “the Inquisition” remains an image of terror to be conjured up by those who claim to defend the vacuous concept of freedom of speech.

To fight against error one needs to possess the truth. Thus to battle a negative historical myth, one needs access to truthful historical sources. Inquisition by the historian Edward Peters is one such honest source. In setting out the tone of his work in the Introduction, Peters prepares his reader to confront the Inquisition libel by comparing myth and history in the following terms:1

(9-10)

Myth may accept or reject history, but, because it is myth, it cannot refute history on any other grounds other than comparable historical criticism. This is a book of history and is submitted as history, both the history of part of the past and the history of myths about the past.

This work is then a work which seeks to not only account for the raw historical details about “the Inquisition”—or rather, the inquisitions—but also seeks to relate and disentangle the history of the negative myth that has poisoned the historiographical well. It ought then to be evaluated on these honorable terms.

After providing intriguing exposition regarding the Roman process of inquest, the author recounts how this process was adapted by the Church in the centuries following the conversion of the Empire into that of inquisition. It arose, as he relates, in the Middle Ages as a response to the rise of heretical sects such as the Cathars and Waldenses, and one that was considerably more balanced than contemporary attempts to crush these movements by popular upheavals or the civil arm. He is moreover careful to point out that this practice was a localized office:

(68)

The earliest inquisitors named by bishops and popes held individual charges, and at no time was there a centralized office or authority that may firmly and unequivocally be termed the Inquisition. Such organized institutions did emerge in Spain at the end of the fifteenth century, in Portugal in 1536, and in Rome after 1542, but no medieval supervisory and organizing office existed in this sense at all. Thus, it may be more accurate to speak of medieval inquisitors rather than a medieval inquisition.

Despite this being the truth of the matter, the decentralized nature of this institution—as well as the national rather than international organization of its descendants—would be ignored by later polemicists, who created the myth of “the Inquisition” as a seemingly unified and omnipresent force that performed shadowy, sinister deeds in the name of religion. That assault, however, only came about later in history during the Protestant Revolution, which held the Spanish Inquisition in particular hatred.

As much of the inquisition literature and public imagination is concentrated on that particular national variety, Peters accordingly spends much time evaluating it. What he offers the reader is a copious amount of information which completely devastates the conventional understanding of the Spanish Inquisition. Consequently, not all of it can be conveyed in this review. Some of the more relevant points, however, will be here assessed.

In assessing the Spanish Inquisition and the other inquisitions of post-Protestant Revolution Europe, the author establishes that these were not the only form of religious tribunal in Europe at the time. Moreover, as Peters demonstrates, they were comparatively lenient when weighed against their contemporaries:

(87)

The fact that in much of Mediterranean Europe these offenses were prosecuted in ecclesiastical courts, often inquisitorial tribunals, should not obscure the equally evident fact that they were prosecuted as vigorously, and usually with less care, in other tribunals throughout Christian Europe in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Indeed, recent research has suggested two important features that distinguish the Spanish Inquisition from other courts that tried comparable offenses: the first is that the Spanish Inquisition, in spite of wildly inflated estimates of the numbers of its victims, acted with considerable restraint in inflicting the death penalty, far more restraint than was demonstrated in secular tribunals elsewhere in Europe that dealt with the same kind of offenses. The best estimate is that 3,000 death sentences were carried out in Spain by Inquisitorial verdict between 1550 and 1800, a far smaller number than in comparable secular courts. The second is that the Spanish and Roman inquisitions were concerned to a far greater degree with the mind and will of the accused. Inquisitors, like confessors, were trained to examine the mind and the soul, and they appear to have understood their victims far better than their counterparts in secular courts. Such understanding may lead to leniency as often as to harshness.

Thus the Spanish Inquisition killed far less than has been often asserted. For a death toll of 3,000 over the course of a little less than three centuries is far beneath the supposed millions that some polemicists have claimed. Peters also touches on the reason why the inquisitors were not as bloodthirsty as they have been unjustly portrayed as—their intimate concern for the souls of those they interrogated. The fundamentally penitential and rehabilitative nature of the inquisitions is further revealed by details that will surprise those who are only familiar with the negative myth of “the Inquisition”.

For one, the inquisitors tended to be cautious in their examinations of the accused. They were open-minded enough to consider that their suspects may have asserted false teachings not out of spite against the Church, but in ignorance resulting from poor religious formation. As the author remarks:

(111)

…[I]n many cases the inquisitors understood very well that the lack of catechesis or consistent pastoral guidance could often result in misunderstandings of doctrine and liturgy, and they showed tolerance of all but the most unavoidably serious circumstances.

How different is this from the overzealous bloodthirsty fanatics that have been so often portrayed as inquisitors! This level of understanding towards the accused further illustrates that they were more akin to confessors than theological secret policemen.

Another point in which the real inquisitors differed entirely from the popular myth—and indeed from some modern governmental organizations—is that they allowed the accused to obtain a civil defense. Recounting the process of the Spanish inquisitional tribunals, the author states that this would occur after the arrest of the suspect:

(92)

The family of the accused was also formally notified so that it might use its power of attorney to obtain a defense for the accused.

Furthermore, the Spanish inquisitorial prisons were by no means garish hells. As with the inquisitions themselves, Peters informs the reader that they were less arduous than other contemporary prisons:

(Ibid)

Although contact with the outside world was kept to an absolute minimum and the accused was denied all sacraments while awaiting trial, the physical conditions of the Spanish Inquisitorial prisons appear to have been considerably less harsh than those of comparable prisons elsewhere; its later image was colored more by its secrecy than by any actual conditions of extraordinary hardship which it provided.

Moreover, the infamous tortures associated with these places have been largely drummed up; the historical record indicates that “inquisitorial torture appears to have been extremely conservative and infrequently used” (Ibid).

Such facts only further make apparent the true mission of the inquisitions—the reconciliation of those lead astray by error to Catholic truth. The inquisitions were not obsessed with punishment; their enemies were. For while the enemies of the inquisitions depicted dark cells and sinister tortures to highlight and exaggerate the supposedly unique cruelty of these institutions, the inquisitions portrayed an entirely different image of themselves:

(225)

The iconography of the Inquisition…did not often depict the execution of those condemned to death, because the execution was less important to the Inquisition than the assertion of truth and the penitence of its enemies.

From this survey, it is evident that this book has much to offer to the diligent reader. Yet, as has been indicated previously, Peters does not limit himself to telling an accurate story of the inquisitions, but also provides a hefty account of how the myth of “the Inquisition” came to be. He then has not only granted us an excellent study of history, but also a fascinating window into the process of historiography. And on the other side of that window there is a grave warning for ourselves: when circumstances and powers favor distorting this process, it is an easy thing to distort. One then must regard the phrase “historical objectivity” with great skepticism in our time. This is a work then to be recommended to the earnest student of history, and to the Catholic student of history especially.