Available from Ignatius, Abebooks, and Amazon

Book Length: 154 pages

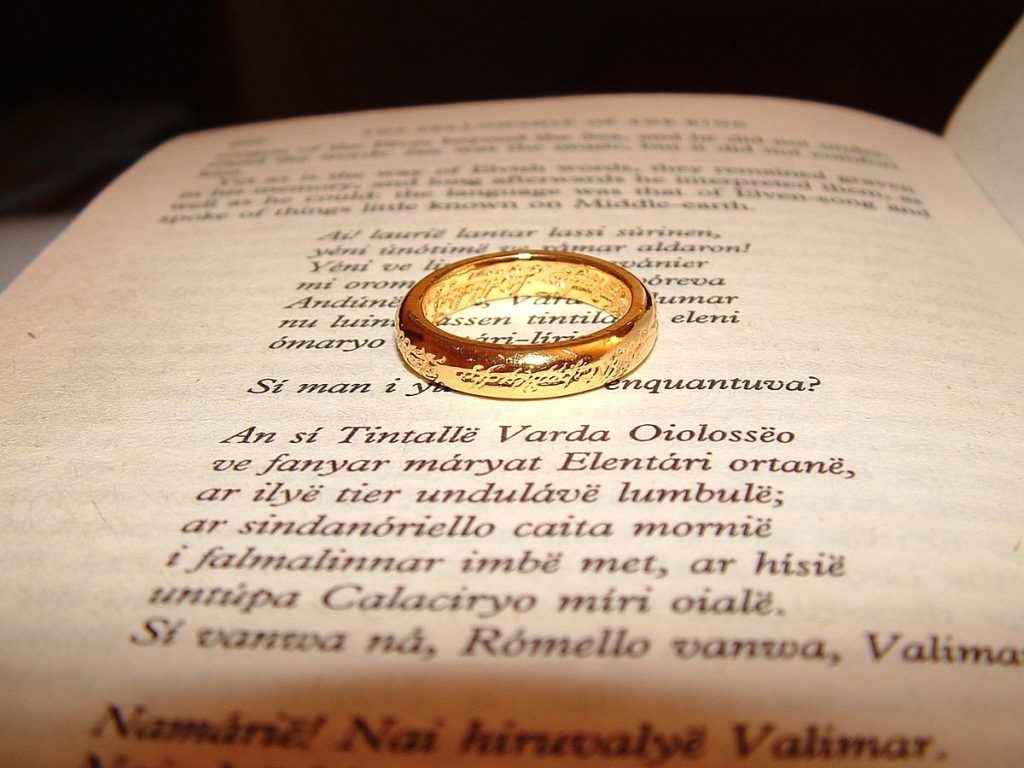

Assuredly, J.R.R. Tolkien needs no introduction. But in the decades since he left this world, there have been many attempts to interpret his vast literary corpus—from his essays and short stories to his The Lord of the Rings trilogy, the apex of his career, to his unfinished Silmarillion. And where many have failed, the author Richard L. Purtill succeeds in his brilliant analysis J.R.R. Tolkien: Myth, Morality, and Religion. It will therefore be examined here in some detail.

Tolkien was indeed a myth-maker, but he never sought to establish any authority for his mythos above the Catholic Faith. Such a distinction is important to understand, considering that there are those on one hand who seek to claim that he did so in order to covertly “resurrect” paganism, while narrow-minded Catholics and members of other denominations on the other hand interpret the presence of magic in Middle-earth too literally and come to the conclusion that he attempted to baptize wizardry and witchcraft. Both perspectives fail to realize that Tolkien had quite a different intention, as Purtill explains:1

(112)

As a writer of fiction, a creator of legend, Tolkien claimed a ‘sub-creator’s’ freedom to explore possible variations on the themes of the original creation—the same freedom he gave the Ainur in his creation myth. So far as his beliefs about the primary world were concerned, Tolkien was a traditional, orthodox Catholic. So far as his subcreated world was concerned, he claimed the right to say, not how things are, but how, within the limits set by his fundamental beliefs, they could be.

To separate, as some have attempted, Tolkien’s beliefs from his work is preposterous. He did not merely write to write; he wrote to convey Christian belief in allegorical language. And though one might retort that this is not possible because Tolkien was against allegory, Purtill demonstrates that his statements in this direction indicate that he was opposed to strict allegory. This sort of narrative is one in which “philosophy or fiction is dressed up as a story” and requires that “each person or event ‘stands for’ some idea or fact of the real world” (17). Tolkien’s use of allegory is nothing of this sort. The Orcs and Goblins are not meant to be German soldiers from either World War, and neither do the Wizards correspond to real-world occultists.

The allegorical language of Tolkien’s works is therefore figurative, not exact. They are “variations”—not reproductions—of the “original creation”. In other words, they are fictional subcreations that embody higher Catholic truths. Only when this is understood can the mythic, moral, and religious significance of his writings be accessed.

Frodo, the main protagonist of The Lord of the Rings, has been noted by some to have a Christ-like role. Purtill has much to add in this regard, with the following passage being a particularly masterful example:

As Frodo comes closer to Mordor, he is led into a trap by Gollum and rendered unconscious by the bite of a giant spider, then captured by the ones who guard Mordor. His physical sufferings parallel those of Christ: he is imprisoned, stripped of his garments, mocked, and whipped. Even after Sam rescues him and they resume their journey to the fires of the Crack of Doom to destroy the Ring, Frodo’s sufferings continue. He is terribly weary, and the Ring becomes a more and more intolerable burden. Frodo’s journey now powerfully recalls Christ’s carrying of the Cross.

Whether this is intentional on Tolkien’s part is hard to say. As a Catholic of a rather traditional kind, Tolkien would have been familiar with the Rosary, a form of prayer in which beads and spoken prayers occupy the body while the person praying meditates on various ‘mysteries’—incidents from the life of Christ and his mother, Mary. The five ‘sorrowful mysteries’ are Christ’s agony of mind in the Garden of Gethsemane, his whipping by the Roman soldiers and their crowning him with thorns, the carrying of the Cross, and Christ’s crucifixion and death. These are the natural images of suffering for any Catholic, but they also represent all the basic kinds of suffering: mental anguish, physical pain, being mocked, wearily carrying a burden, death in agony.

(57)

This profound reading further illustrates the rich depth of Tolkien’s storytelling. For while some Catholics have rightly seen in Frodo a priestly figure, they typically support their argument by referring to the Way of the Cross imagery found in the last part of the hobbit’s journey. While this is indeed good evidence, it would be worthwhile to include Purtill’s observations in this argument. For Purtill’s demonstration of the thematic unity of the whole Mordor sequence by means of its parallel to the Passion is one that brings out the sublime subtlety of the text’s Catholic morality.

It also directs further attention to Frodo’s significance as a type of Christ in the Biblical sense. As Church tradition instructs us, there were various types of Christ in the Old Testament, men who in some manner embodied the qualities and life of the Savior to come.2 One of these was Moses. He led the Israelites out of physical bondage, just as Jesus has led and presently leads men out of spiritual bondage. Yet, this great prophet was forbidden to step within the Promised Land because he had mistrusted God. Does Frodo then not resemble Moses in this sense? For he, like Moses, came very close to completing his divine mission—but failed. Thus he holds an allegorical resemblance to Christ, but not an exact correspondence to the perfect God-Man.

In a similar vein, Galadriel is a type of the Holy Virgin, as can be surmised from the following excerpt:

About Galadriel, Tolkien makes an interesting comment in a letter:

“I think it is true that I owe much of this character to Catholic teaching and imagination about Mary, but actually Galadriel was a penitent: in her youth a leader in the rebellion against the Valar (the angelic guardians). At the end of the First Age she proudly refused forgiveness or permission to return. She was pardoned because of her resistance to the final and overwhelming temptation to take the Ring for herself.”

Galadriel is like Mary, the mother of Christ, in her humility, her willingness to be a humble ‘handmaid of the Lord’ rather than trying to be Queen. As with Mary, humility receives its reward: ‘The one who humbles himself shall be exalted.’ But Galadriel is unlike Mary in having previously refused to learn this lesson and in having to repent and relearn.

(85-86)

Though Galadriel in many respects is like Mary in her qualities, the allegory is not exact as per Tolkien’s own admission. Our Lady never fell; Galadriel did, but repented. This places Galadriel in a position akin to the figures of Mary in the Old Testament such as Eve (or even St. Mary Magdalene in the New), thus being related to the Queen of Heaven by type.

Both Frodo and Galadriel are then not direct allegories for Christ and Our Lady—they are instead figures of the King and Queen of Heaven. Such is Tolkien’s method, which differs quite expectedly—and drastically—from that of his friend C. S. Lewis, whose character Aslan in The Chronicles of Narnia is a literal allegory of Christ.

Alongside his exploration of religious allegory in Tolkien’s work, Purtill also spends considerable time examining the deeper moral values within those texts. Of these, there is a particularly thought-provoking discussion of suicide when the author discusses the fate of Denethor in The Return of the King. He writes:

If he could only, as Pippin does, make a generous gesture without thought of consequences or, as Gandalf does, serve the good of others selflessly, he could be a great force on the side of good. But he trusts to himself and his own power and cunning, and when these fail, he despairs and kills himself. Just before he dies, he says:

“I would have things as they were all the days of my life…and in the days of my long-fathers before me: to be the Lord of this city and leave my choice to a son after me…But if doom denies this to me, then I will have naught: neither life diminished nor love halved nor honor abated.”

This is the true voice of pride: either things as I want them or nothing. It is the voice of the spoiled child, the adult egomaniac, the sinner who will not repent.

(63)

Is this not the true horror that suicide ought to inflict upon us? Unfortunately, modern society is colored by a great sympathy for this lamentable act. Too often in these past decades it has been portrayed in terms akin to that of martyrdom; we are supposed to ignore that it is an act of pride precisely because it is a tragic act.

It is indeed tragic, but there is nothing heroic in it. For this forfeiting of life evades the possibility of a better future by surrendering to the conclusion of despair. It is a terrible ultimatum to the Author of Life: “either things as I want them or nothing.” We did not bring ourselves into this world; thus, where do we claim the right to take ourselves out of it? Life is a gift of God, no matter how many sinful decisions—whether made by ourselves or not—mar our ability to enjoy it as we were intended to. Assuming there is no presence of a mitigating factor such as extreme mental illness, the act of suicide is therefore irredeemably selfish in the eyes of God and so ought to be in the eyes of men.

In closing, this analytical work will prove a valuable resource to those who wish to connect on a deeper level with the true spirit that animated this rightful heir to the epic writers of the past. It is succinct while managing to communicate profound ideas, and does so in a manner approachable to both the academic and the non-academic mind. The only objection to be noted is that some passages evidently show that Purtill unfortunately embraced a post-Vatican II mentality. Otherwise, it is to be recommended to all who love the work and world of Tolkien.

-

All quotations of this text are provided from

Purtill, Richard L. J.R.R. Tolkien: Myth, Morality, and Religion. Harper & Row. 1984.

-

See for reference the section entitled “Typical sense” in Maas, Anthony. “Biblical Exegesis.” The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 5. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 1909.