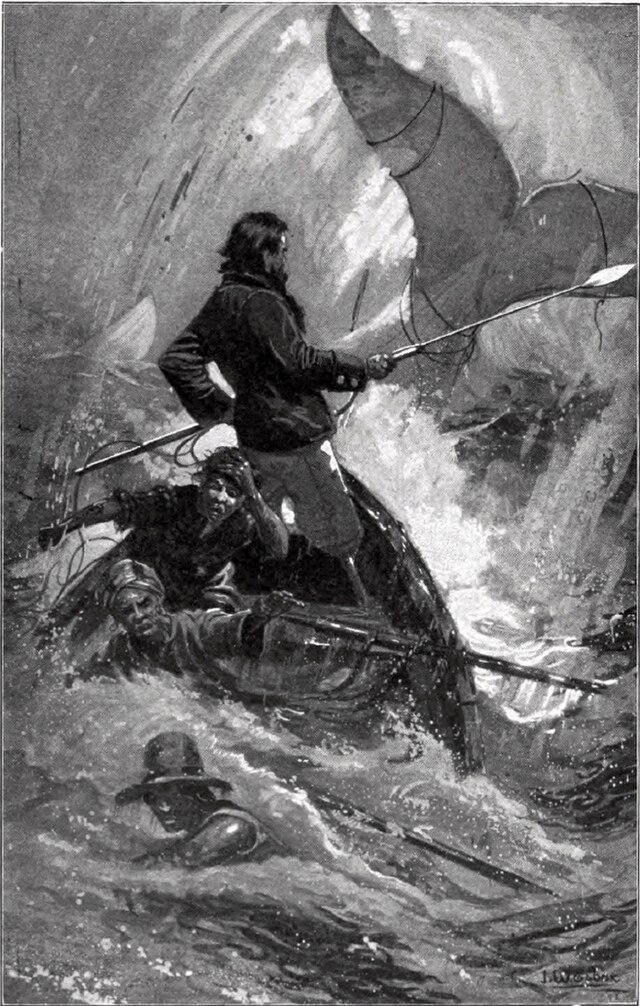

Illustration of the final chase of Moby-Dick by I.W. Taber

Available from Ignatius Press and Amazon

Book Length: 706 pages

Adventure and inquiry were critical components of the old America—and they are vital components of Melville’s epic, Moby-Dick. Since the nineteen-sixties, the culture of that old America has been obscured, derided, and betrayed. It should not be a surprise, then, that the literary interpretations of this classic since that time have followed this sorry trend,1 for to successfully destroy a culture one needs to eliminate or bastardize its art as well as its people. But to revive a worthy culture’s art is not only a good in itself; it also revives the spirit of its people. Thus, rediscovering the truth of Moby-Dick is a necessary element in reclaiming American culture from the confusion it currently suffers from.

As this story begins and ends so strikingly in the company of its protagonist, it is only proper to begin an analysis of this work with him. Ishmael serves as both the narrative voice of the story while fulfilling a prophetic role, though he is no prophet of the true religion. He is an uncertain prophet, for unlike the true prophets or their impostors he cannot even seem to agree with himself on a singular message to his audience. At times, he evidently conveys a moral, as if to call his reader to examine themselves; at others, he expresses doubt in his ability to reach truth and comes to no closed conclusion. Thus to some readers, his intellectual and spiritual meanderings throughout the story may in some respect echo Pascal’s famous criticism of Descartes: “Descartes, useless and uncertain.” But such uncertainty is representative of the indifferentism of Ishmael’s culture—the antebellum United States, a republic that prided itself on diversity of thought and a rejection of orthodoxy. It is this pitfall which was—and still is, for it continues—a far more damning societal sin than slavery. For that kind of slavery was of the body, but indifferentism has the effect of opening men’s minds so wide that they will easily fall for the intangible chains of fealty to a tyrant—just as Ishmael and the crew of the Pequod fall under Ahab’s sway.

Ishmael is, however, not the only misguided prophet in Melville’s epic. Among the others, there are two who like Ishmael assume biblical names—Elijah and Gabriel—but these are clearly madmen rather than genuine or even uncertain prophets. Respectively, they appear near the beginning and the end of Moby-Dick, as if to bookend the foretold doom of Ahab and the Pequod. In reference to their papers to board the Pequod, Elijah ominously asks Ishmael and Queequeg, “Anything down there about your souls?” (130) and Gabriel warns Ahab to “beware the blasphemer’s end!” (378).2

In some manner, their omens recall the desperate cry of a mad prophet from history. This madman was a Jewish peasant who held the same name as the Savior. He preached the fall of Jerusalem to his people for a period of seven years. Despite mockery and even lashings, he still cried out “Woe to Jerusalem!” to all who could hear him. He would continue his cries during the final siege of that city, during which he was killed. Such was related by Josephus, and on this subject the eminent Bossuet considers the possibility that “the Divine vengeance had, as it were, become visible in this man, who lived only to pronounce its decrees.”3

Moreover, Bossuet states that, concerning this Jesus:

(Bossuet 134-135)

It seemed as if the name Jesus, a name of salvation and peace, was to prove a fatal omen to the Jews, who had despised in the person of our Savior; and as those ungrateful wretches had rejected a Jesus, Who proclaimed to them grace, mercy, and life, God sent them another Jesus, who had nothing to proclaim to them but irremediable calamities, and the inevitable decree of their ruin.

Much in the same manner, one can interpret the role of these soothsayers of doom as being messengers of the Divine vengeance. Though this Elijah also opposes a wicked man named Ahab, he has no promise of hope for his hearers; instead of announcing the joy of Christ to the handmaid of the Lord, this Gabriel announces death to a man who rebels against God. And despite their madness, there is truth in both of their actions. For in fact Ahab does commit blasphemy against God, for behind his antipathy towards the whale Moby Dick is a Manichean belief that this creature is the physical incarnation of evil. In one of his great monologues, he says:

(208)

He tasks me; he heaps me; I see in him outrageous strength, with an inscrutable malice sinewing it. That inscrutable thing is chiefly what I hate; and be the white whale agent, or be the white whale principal, I will wreak that hate upon him.

His crew are not excused from the guilt that hatred carries with it. For they are enticed by his quest and join in it, making them partakers of his sin. Thus, in a scene in “The Quarter-Deck” that resembles a mock Mass, impious Ahab is able to cry out to a cheering crowd of his men: “God hunt us all, if we do not hunt Moby Dick to his death!” (211).

Paralleling the hunt for Moby Dick is Ishmael’s hunt for truth. Much of it occurs through his retrospective narration, which is largely concerned with discussing whale-related minutia. One may ask: what is the purpose in this? Ishmael, like Ahab, sees in the whale a great mystery—in Ahab’s words, some “unknown but still reasoning thing” which has imprinted itself on the creature. Though Ahab’s quest is a physical revenge plot with a metaphysical underpinning, Ismael tries to conquer it intellectually. He gathers an encyclopedic quantity of information about whales and whaling and frequently attempts to draw some higher meaning from it.

For instance, after relating how the crew hoists the heads of a right whale and a sperm whale on opposite sides of the Pequod (a practice believed to bring whalemen good luck) he comments:

(388-389)

As before the Pequod steeply leaned over towards the sperm whale’s head, now, by the counterpoise of both heads, she regained her even keel; though sorely strained, as you may well believe. So, when on one side you hoist in Locke’s head, you go over that way; but now, on the other side, hoist in Kant’s and you come back again; but in very poor plight. Oh ye foolish! throw all these thunder-heads overboard, and then you will float light and right.

A frustration with this practice and how it balances the ship in a “very poor plight” is analogized to represent Ishmael’s dissatisfaction with those two metaphysicians. Presumably, this is because he holds that attempting to balance Locke’s views with those of Kant is a fool’s errand. Better then, as he states, to “throw all these thunder-heads overboard”—to throw the heads of the two most venerable whales and the two “heads” of the so-called “Enlightenment” overboard in order to regain stability. For Ishmael this stability appears to be found in some sort of humility before the “unknown yet reasoning thing” that fashions and governs all life, which for him is best embodied in the whale.

He is not then a voice against philosophy as such; he rather sees his own vision as the true philosophy. But not only is he a sailor-philosopher—he is also a sailor-metaphysician. Since he attempts to understand all that exists by means of the whale, he is attempting to seek out the first cause of beings. And it is precisely the study of being and the search for the first cause that unite all metaphysicians.4

Yet no matter how illuminating such passages may be, both Ahab’s and Ishmael’s quests prove futile. For to embark on this search solely within the universe is vain—one must reach outside it. As St. Augustine comments:5

I had sought Him in the body from earth to heaven, so far as I could send messengers, the beams of mine eyes. But the better is the inner, for to it as presiding and judging, all the bodily messengers reported the answers of heaven and earth, and all things therein, who said, “We are not God, but He made us.”

Just as one may understand something of the real Shakespeare by reading one of his plays, one may indeed understand something of God by observing his creatures. Yet, the created is not the creator; a reader of Shakespeare does not have access to the man, only his works. In a similar manner, one who observes the power of the whale and sees something awe-inspiring may indeed have obtained some faint indication of the power of God, but it is not complete understanding. The metaphysical journey will therefore only find its safe harbor in Heaven, because to be united to Him is to be united to Ultimate Being. Otherwise, anyone who seeks to pierce beyond that veil in seeking out being in all the other beings, whether man or whale, is doomed to ruin.

But is this not the error so often repeated around us? So many people seek the ultimate fulfillment of their being in possessions, in sensuality, in power, and so on, when that fulfillment can only be found with God. At least the animals follow what has been ordained for them from above; but how many men are proud and follow their fallen nature to what lies below! Or, as Ishmael would put it: “There is no folly of the beasts of the earth which is not infinitely outdone by the madness of men” (450).

Melville himself may very well have intended to gesture in this direction, for throughout the work there are numerous references to the Cross and Calvary. The most recurring and powerful of these is the motif of the three masts of the Pequod, which obtain their full meaning in a scene near the end where, during a violent thunderstorm, lighting strikes them. Ishmael, describing the visual effect, relates that “each of the three tall masts was silently burning in that sulphurous air, like three gigantic wax tapers before an altar” (580). There are evidently Catholic connotations here, though Melville was not Catholic—the connection of the three cruciform masts are akin to the three crosses of Calvary, and the “tapers before an altar” call to mind the Mass, which is Calvary unbloodily re-presented.

Whatever holiness in the burning “three tall masts” inspires the crew to fear; Ahab, however, remains amazingly untouched. Amid the turmoil of the storm and darkness of the night sky, he boldly declares to his men that this event is not an omen against hunting Moby Dick, but instead an invitation to destroy him. The crew are then faced with a choice: to follow their just fear or the self-serving interpretation of their mad captain. Perhaps there could have been a legitimate usurpation on the Pequod—but rather than overthrow Ahab, the crew are persuaded by him to battle the whale. It is therefore in the process of ambivalence to demagoguery that the real tragedy of Moby-Dick lies: the path which begins with a Montaigne but ends in a Robespierre.

This then is certainly a work worthy of our attention, even if it were not a classic. Catholic and non-Catholic readers alike will therefore reap grand dividends if they attentively read this challenging epic. The Ignatius Critical Edition version of the text is especially recommended for the reader interesting in undertaking this literary voyage. It is devoid of the ideological rot noted at the beginning of this review, and its insightful essays demonstrate how the classical tradition is not dead, but is still living and has much yet to say.

-

See for reference the chapter “Moby-Dick: Cutting a Classic Down to Ideological Size” in Peter Shaw’s excellent Recovering American Literature.

Shaw, Peter. Recovering American Literature. Elephant Paperbacks. 1994.

-

All quotations of Moby-Dick are lifted from the Ignatius Critical Editions version of the text.

-

Bossuet, Jacques-Bénigne. The Continuity of Religion. Translated by the Rt. Rev. Mgsr. Victor-Day. p. 134.

-

See for reference the following remark from Gilson:

Gilson, Étienne. The Unity of Philosophical Experience. Sheed and Ward. p. 313.

It is an observable character of all metaphysical doctrines that, widely divergent as they may be, they agree on the necessity of finding out the first cause of all that is. Call it Matter with Democritus, the Good with Plato, the self-thinking thought with Aristotle, the One with Plotinus, Being with all Christian philosophers, Moral Law with Kant, the Will with Schopenhauer, or let it be the absolute Idea of Hegel, the Creative Duration of Bergson, and whatever else you may cite, in all cases the metaphysican is a man who looks behind and beyond experience for an ultimate ground of all real and possible experience. -

The Confessions of Saint Augustine, Book X. Translated by E.B. Pusey. Modern Library. 1949. pp. 201-202.