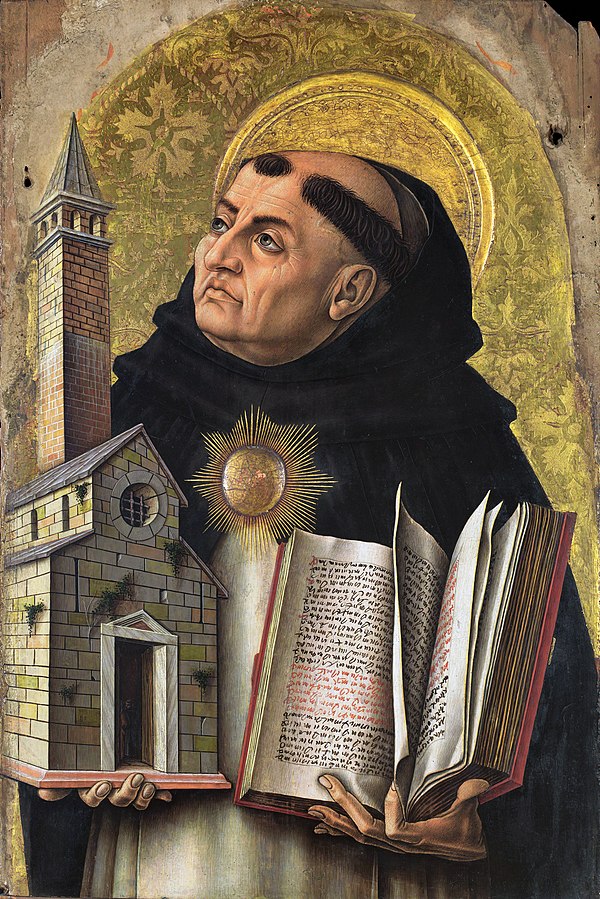

Saint Thomas Aquinas by Carlo Crivelli

Available from Angelus Press and TAN Books

Book Length: 638 pages

Among the challenges of the present time, there is an immense gap of knowledge not only in theology, but in philosophy as well. As some animals are born into this world blind, such as the cat for instance, the overwhelming majority of persons today enter the “adult world” in a state of intellectual blindness, for so prevalent are the errors of modernism and post-modernism that one is raised by default in our society to hold a steadfast belief in these absurd doctrines without even knowing their names. The ignorance which many speak of these two sciences is startling, but it can be remedied by a return to the sound teachings of St. Thomas Aquinas, whom Pope Leo XIII praised in Aeterni Patris as “the special bulwark and glory of the Catholic faith.”1

Indeed, a good number of Catholics in our age have had their intellectual blindness cured by rediscovering his wisdom. How excellent is it in turn, when such Catholics marry and have children, and impart the truths of the Angelic Doctor to them!

Reading—never mind teaching—the Summa Theologiae, however, presents a slew of difficulties for even educated persons; thus, this book, which is written for the layman in mind, is excellent in making the teachings of St. Thomas accessible to all. Given that this work exposits the entirety of the Summa, only a cursory evaluation can therefore be given here.

On some level, the importance of love and hate is well-known in our age; but it is difficult to find two words subject to more abuse than these, aside from the two that compose the name of the Savior. Love is commonly thought, like hate its opposite, to be an emotion rather than an act of the will—here the fundamental differences between Catholic and worldly perceptions of these concepts begin. In refusing to see love and hate as choices, the modern worldling makes themselves the slave of their emotions, which pass like the tides of the sea. Thus to them, infatuation is love and parental discipline is hate. Yet despite these errors, they are correct in believing that one should be a loving person rather than a hateful one. There is a law written on men’s hearts, and with that law there is the knowledge that we are destined for love, as in the third chapter of Part III of this work it is written:2

Man was made for love. He cannot rest in hate.

(361)

This is simply inexplicable to the modern, though he or she agrees with it in a certain sense. The false science of Evolutionary Psychology (or any other materialist reductionism, for that matter) will never be able to adequately answer this question, which burns within each one of our hearts: why do I love? Or, as the pagan Virgil wrote:3

Love alters not for us, his hard Decrees,

(Eclogue X. 92-99)

Not tho’ beneath the Thracian Clime we freeze;

Or Italy‘s indulgent Heav’n forgo;

And in mid-Winter tread Sithonian Snow.

Or when the Barks of Elms are scorch’d, we keep

On Meroes burning Plains the Lybian Sheep.

In Hell, and Earth, and Seas, and Heav’n above,

Love conquers all; and we must yield to Love.

But as Virgil could not understand the true cause and meaning of our intense longing for an infinite love, so too are the post-Christian pagans of the modern world trapped in a similar fog. We thirst for an infinite love, because we were made out of love by an infinite God, who is love Himself. As St. John the Apostle wrote: “He that loveth not, knoweth not God: for God is charity” (1 John 4:8). Explaining the nature of true love further, and why hate is its opposite, Father Healy informs us that:

Love brings fulfillment and rest in the goodness of God in Himself and in His world. But hatred can only bring an agonizing frustration. Hatred naturally despises what man most naturally loves—the good. But hatred cannot destroy what it hates—the good. The goodness of God is eternal. The manifestation of His goodness in the world goes on forever despite the evil of men.

(Ibid)

Love fulfills because it builds; in man, the image and likeness of God, this is manifest in many different ways. We see, for instance, that love has moved the work of great artists like Bernini or Dürer. But we can find more everyday examples than these; for in the case of the family, the love between husband and wife brings new human life into the world.

The highest form of love, or charity, is that which is aimed towards God Himself. As is related in this same chapter:

God asks for man’s love through charity not in order to take any good thing away from man but in order to give all good things to man.

(347-348)

How beautiful was the understanding of St. Francis of Assisi in this regard, who repeated often to himself, “My God and my all!” in adoration of the Presence of God. For God really is our all, because he is Goodness itself, and He is Love itself. Therefore, what He asks of us does not restrain us in the real sense of that term; rather, it liberates us. Even if one is called to celibacy, say in the case of religious life, the vow of chastity that comes with it—so hated by the world—liberates these chosen souls from worldly concerns so that they may more easily obtain union with God. Despite, however, the transcendent power of the love of God, it is still possible to have one’s judgment clouded concerning Him, as we see all around us. Formulating exactly how this occurs, the text instructs us that:

Unfortunately man does not see God clearly in this life. Hence it is possible for a sinful man to consider God only as an avenging Judge forbidding sin and inflicting punishment. As long then as the sinner refuses to give up his sin, God will appear as something evil to himself. In this way it is possible for man to hate what is supremely lovable in itself.

(359)

In such a situation, the sinful habits of the sinner are the fog which prevents him from perceiving the goodness of God, and in this fog his view of Him gets warped. It is this warping which is essential to that horrible thing Scripture terms hardness of heart.

Under the dominion of Satan, such persons see the purity of life which will one day be transformed into the “liberty of the glory of the children of God” (Romans 8:21) as an insufferable slavery, for they have preferred some lesser good or disordered thing to the “abiding Goodness which holds out/Its open arms to all who turn to It” (Purgatorio III. 122-123).4 Poor souls! How many today live in such a miserable state! But even they, who dare raise their fists at Heaven, can still receive the gift of conversion. Indeed, God desires for us to pray for such persons and edify them, if possible, by our charity.

So that we may avoid such a miserable course of life, we must regulate our actions. But to achieve this, we must understand the roles which joy and pleasure take in our lives, and accordingly order our days in His peace. In the fourth chapter of Part II, Father Healy touches on this subject, writing that:

Since pleasure or joy is the goal that man aims at in his loves and desires, the morality of our pleasures is of great consequence in our lives. Their morality is to be judged by the standard of right reason. If they lead to man’s final goal, the vision of God, they are in accord with right reason and therefore good. If they turn man away from his final goal, then they are not in accord with right reason and so are evil. The highest pleasure possible to man is the enjoyment of God in the beatific vision of God. All other pleasures are subordinate to this final pleasure or joy. The good things of this world are only a foretaste of the joy of Heaven. It is the task of reason to determine whether or not earthly pleasures lead to the joy of the vision of God.

(207)

And this is where sound philosophy, which strengthens and guides our reason, can aid us the most. The categorization and syllogisms of scholastic philosophy, of which St. Thomas represents the pinnacle, do not need to be memorized to their minutia to benefit us. Nor, in like manner, does the comforting stability of moral theology need to be known in exact details by the faithful as the priest does. We ought to be familiar with them to the point that we can truly say that we live by the spirit of the law rather than the letter of the law.

To know the categories of the virtues, for instance, and to know their opposites, enables us to ask with greater clarity in our prayers for what we truly need, and to recognize our poverty before the Giver. Moreover, they help us to understand what other actions we may take to grow more virtuous, and in like manner to avoid that which makes us more vicious. Living in such a manner—a life really examined—frees us to live how God really wants us to live and to love how He intends us to love. For contrary to the modernist opinion that the dignity of man, predicated on his being made in the image and likeness of God, is somehow “infinite” and inviolable, the wisdom of the Thomist school answers in the following: it is living in the state of grace which makes us the image and likeness of God. As Father Healy, in chapter ten of Part IIb, asserts to the reader:

As long as grace and charity remain in man’s soul, man is the image and the likeness of God.

(439)

The soul of the sinner in the state of sin, then, may be compared to a car in a junkyard or a corpse in a grave; for if she was ever in the state of grace, really did possess the image and likeness of God but has lost this—to her own fault. She was alive, and now she is dead. Now, in the case of an unbeliever who never was baptized, there is a degradation of sorts. This soul really ought to belong to Christ, but as a result of the hardness of men’s hearts she has been rested from Him. There is, however, still a potential for her to possess the life of grace, because this is what man is meant to have. In this, there is a resemblance to an abandoned pair of shoes; they were meant to encase human feet, and there is the very real possibility that one day they will again fulfill that purpose for which they were made. Of course, there is nothing of an abstract probability in the case of souls. The Presence of God, though present in holy places—such as a sanctuary or a church—more so than others, is accessible to just and sinner alike, anywhere in the world. It is a matter of real choice rather than raw chance, as the world is governed by Providence, not probability.

In closing, all Catholics should read this work, if not in its entirety at least in part. The brilliant explanations of the thought of the Angelic Doctor are complemented by both authors’ skillful command of diction and the language of allegory. This preserves the attention of the reader, and moves them to further consider the truths which are recorded on these pages. Truth here is painted in all its glory (insofar as is possible in writing), while evil is painted in all its hideousness; this is especially needed in our time, where the boundaries between these opposites are often obfuscated by the false visions of reality provided by the institutions. This work, therefore, is a superb gift to modern man—it is a passing of the torch of the greatest mind of the Age of Faith to our Age of Darkness.

-

“Among the Scholastic Doctors, the chief and master of all towers Thomas Aquinas, who, as Cajetan observes, because ‘he most venerated the ancient doctors of the Church, in a certain way seems to have inherited the intellect of all.’ The doctrines of those illustrious men, like the scattered members of a body, Thomas collected together and cemented, distributed in wonderful order, and so increased with important additions that he is rightly and deservedly esteemed the special bulwark and glory of the Catholic faith. With his spirit at once humble and swift, his memory ready and tenacious, his life spotless throughout, a lover of truth for its own sake, richly endowed with human and divine science, like the sun he heated the world with the warmth of his virtues and filled it with the splendor of his teaching. Philosophy has no part which he did not touch finely at once and thoroughly; on the laws of reasoning, on God and incorporeal substances, on man and other sensible things, on human actions and their principles, he reasoned in such a manner that in him there is wanting neither a full array of questions, nor an apt disposal of the various parts, nor the best method of proceeding, nor soundness of principles or strength of argument, nor clearness and elegance of style, nor a facility for explaining what is abstruse.”

Leo XIII. “Aeterni Patris.” (August 4, 1879). §17.

-

All quotations from this text are provided from:

Farrell O.P. S.T.M., Fr. Walter, and Martin J. Healy S.T.D. My Way of Life. Society of the Precious Blood. 1952.

-

The John Dryden translation of Eclogue X is here quoted.

https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/The_Works_of_Virgil_(Dryden)/Pastorals_(Dryden)/Book_10.

-

I utilize here the Ciardi translation of Dante’s Purgatorio.