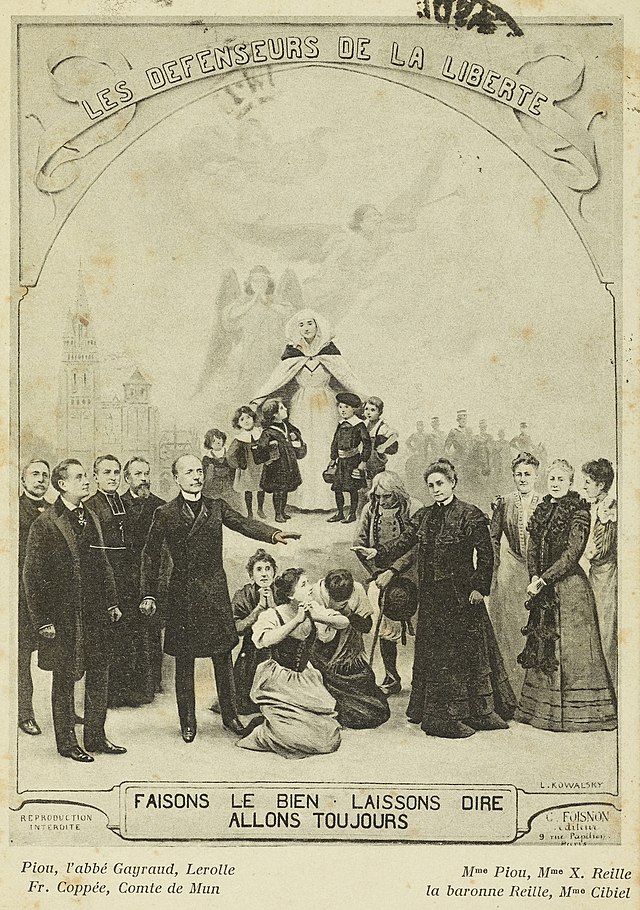

“Faisons le bien laissons dire allons toujours” by Léopold-Franz Kowalski

Available from the publisher, Mediatrix Press and Amazon

Book Length: 444 pages

The history of what has been—and may rightly be termed—the First Industrial Revolution has been subject to all sorts of erroneous presentation. The most grievous of these is the omission of the activities of the Church during that troubling yet exciting era, which began in the nineteenth century and terminated roughly in the early twentieth. In that space of a hundred years or so, the activities and writings of her enemies, no doubt, are given extensive attention—the Marxists, Darwinists, and Feminists, to name the most prominent. Their false apostles are held up as heroes, while those great men and women who labored in the Lord’s vineyard are shut out from the historical discourse. Such a historiographic crime is remedied by this book, wherein one learns, through the insightful and measured biographies of its subjects, a story almost never told.

To begin with, the work does a thorough job in establishing the historical context that surrounds the thirteen great lay apostles it portrays by the means of a lengthy yet worthwhile introduction. Contrary to the opinion of some traditional Catholics, the Ancien Régime (or Old Order) was far from perfect. As a consequence of the Protestant Revolution, the insecurity of the Church’s temporal position led to a situation in which:1

…[T]he absolute ruler was able thenceforth to bargain with various religious groups and to protect that religion which buckled under and surrendered to him more and more of the functions formerly reserved to religious authorities. Thus in every country, Catholic as well as Protestant, the Church of the realm was identified popularly with the Old Regime until the French Revolution of 1789. French kings nominated and, for all effective purposes, chose the bishops of the Church. So it was in most of the other countries of Europe. The king enforced canon law, or refused to do so, as he saw fit; his permission had to be obtained before a papal letter could be read from the pulpits of the churches in his realm.

This interweaving of Church and State may not be a bad thing in the abstract, but in the concrete case of Europe in the eighteenth century it turned out badly for the Church. The rulers were not interested, by and large, in the religious welfare of their subjects. They looked upon the Church as a department of State, and religion as a means for keeping their subjects content.

(1-2)

Neil articulates here a historical truth grounded in realism—a truth heavily important for understanding that a simple return to the past was not the answer to the Revolution. Those who would blindly uphold monarchy fall right into this trap, for such unprincipled endorsement leads souls to place the principle of monarchy above all things, even the Faith itself.2 It is, no doubt, a very sensible trap as it was during the turbulent period between the Revolution and the First World War. In our time, an age in which man finds himself subject to the imposition of oligarchic plutocracies which scorn altar, hearth, and throne, the temptation to abandon oneself to a romanticized extreme of the opposite is even stronger. Yet history teaches us that monarchy, while a positive and natural form of government, too can be abused and swiftly descend into tyranny. Thus the need for balance presents itself.

This was a point understood by the figures highlighted in this book, for even though they approached the problems of the social order and the relationship between Church and State from differing and even clashing perspectives, they did so from a foundation rooted in their Catholic faith. This guiding light allowed them to condemn the ills in both the old order and the new, while simultaneously providing them the insight necessary to see what could and could not be reconciled. Illustrating this pivotal detail, the author writes:

Catholic lay leaders of the nineteenth century divided themselves pretty well into two groups, conservative and liberal, depending on their attitude towards the society of their age. Among the conservatives we should place De Maistre, Donoso Cortés, and Veuillot as outstanding thinkers. These were men who looked upon their century as radically wrong. On the other hand were liberal thinkers, like Montalembert, Ozanam, Görres—and in his individual way—Orestes Brownson. These were men who looked upon their society as basically sound, men who loved the new liberty and wanted to join it with Catholicism. The two groups were equally loyal to the Church. They differed on a question of policy, on which was the best way to achieve the end they both desired.

(212)

The use of the term “liberal” here is to be distinguished from the common use of that word, for none of the “liberals” listed here were adherents of Liberalism or even Liberal Catholicism, both of which were condemned in their time, and have since been condemned by the Church repeatedly. These men acknowledged the errors of that pernicious ideology, while still seeing good in some of the concepts of the new order. “A Free Church in a Free State”, title to one of Count Montalembert’s speeches, sums up the desire of this party to see the new situation utilized to the fullest. They wished to see the Church united to the State, but in a manner which avoided the potential tyranny of the State which reared itself whenever the clergy were made dependent upon it. For this reason, perhaps it would have been better to label them as republicans rather than liberals.

One of this book’s greatest strengths is that its author is able to effectively communicate the balance between the republicans and the reactionaries, and to show both the positives and downsides of those who held those positions. As much as I personally think that of the two, the conservative faction was more correct in their assertions—in so doing, I disagree here with Neil—I do not fault the republicans. They were not naive nor deluded—as the apostate priest Lamennais and his followers were—but had an understandable reaction to the problems of their time, as the case of Montalembert shows:

Montalembert’s attitude toward democracy was one of resignation. He did not like it, for he thought it a steppingstone to despotism—as it had actually been under Robespierre and Napoleon, and as it was soon to be again under Napoleon III. Nevertheless, he believed that democracy was the form of government for the future, and therefore Catholics had to accept it, baptize it, to find their places in it, to Christianize it.

(70)

However, as the history of Europe and the world has made apparent to all who have eyes to see and ears to hear since the end of the Second World War to our time—a true Dark Age—democracy is almost impossible to baptize. The reasons for this are many, but the most apparent among them is that a Christian democratic republic must subsist in a society that is Christian. Instead of the authentic Catholic Faith, if the vast majority of the people profess a mere nominal Christianity and live like neo-pagans (as is the case in the United States today), this sad fact will be reflected in both political policy and civil discourse. The main reason why the Liberalism of the United States was tenable at all in the past was because its people at least professed themselves to be Christian, and considered Christian moral values something worth defending in both public and private life. With this great barrier torn down during the Satanic Sixties, a deluge of immorality—and the increasing public acceptance of it—was simply inevitable. This process of moral destruction was simultaneous to the one going on in Europe and the rest of the world at the time, albeit the conditions were obviously quite different from place to place, nation to nation.

Looking back to the nineteenth century, when most living under Christendom still cared at least somewhat for Christian belief and morality—notably the lower classes more so than the upper classes—the argument of Montalembert and men like him makes considerable sense. Though his position no doubt did good things for the Church in time, it would be misguided to adopt such a stance today. In that time, these modern republics were greatly swayed by the forces of Judeo-Masonry and central banking; in our time, they are entirely under the control of these enemies of the Church, and are sure to shutter out any true opposition to their aims organized along conventional lines. History has proved the conservative or reactionary party more correct than the liberal party on account of these things and more. For example, Donoso Cortés’ belief that “a new Europe could arise only on the dead ruins of Liberal civilization” was something that probably sounded outlandishly pessimistic to most Catholics who lived both in the eighteen-forties and the nineteen-fifties,3 but sounds prophetic in the twenty-twenties (275). Moreover, according to the self-admission of the oligarchic plutocracies, these “democratic” governments and their institutions are undergoing a severe crisis of legitimacy that, despite their pathetic pleading to the contrary, has revealed to the world that their system is the way to national suicide, not the way of the future.

In our time, we are seeing a similar divide within traditional Catholic circles, along two different lines: symmetric and asymmetric. The symmetrics wish to work within the social and political system to some extent to reform it, while the asymmetrics wish to work outside of it. This dynamic takes on many different forms, and most among ourselves probably fall somewhere along a spectrum of these two general concepts, which concern themselves intimately with how best to live the Faith in these trying times. Resolution and balance is needed between these two groups, as these things were needed for the republicans and the conservatives of the past. There is a need for strong Catholic lay leaders today, as the conditions which led to this need in the past have only gotten more drastic since the beginning of the Crisis in the Church. In order to stay on the right path, these modern lay leaders should imitate the ones found in this book, for their examples are replete with inspiration. Neil only increases the appeal of these figures when he goes beyond treating them in the abstract and provides the reader an insight into their souls, as with this case found in his chapter on the valiant Louis Veuillot:

Louis Veuillot loved his family dearly, and when he was still a young man his wife and four of his six daughters died within four months—a severe trial surely for any Catholic layman. He summed up his reaction to this tragedy simply by saying to a friend, “I am not beaten down because I am on my knees.”

(337)

What humility! What resignation to the Will of God!

This is not the only edifying example which can be drawn from this book, for there are many more which I leave for you, dear reader, to discover for yourself. Sanctity is the greatest means to change a society, and when one is given practical examples even from devout yet non-canonized souls, there is greater motive to follow boldly both the trials and consolations of the spiritual life. But the fruits of the spiritual life cannot be holed up; for Christ has taught us, “You are the salt of the earth. But if the salt lose its savour, wherewith shall it be salted?” (Matthew 5:13). What will we do to help save the souls of our families, friends, and nations?

One will also find the personage of Count Albert de Mun described in this work, a man whose name is unknown even in our circles. But because he is so unknown, I wish to write something of him here, for his social and political work provides a relevant lesson to us. Though he saw through the decadence of the Third Republic and for many years supported the cause of monarchism, he attempted to work within the republican system to the benefit of the Church and his people. In his position as the representative of Pontivy, Brittany, he used his hard-won seat in the Chamber of Deputies to advance positions which anticipated both the teachings of Rerum Novarum and the later idea of Corporatism:

In the debate on a proposal to legalize trade unions in 1883, De Mun presented an amendment in favor of guild organization, and during the course of the debate he spoke so eloquently for his idea that he “created nothing less than a sensation” and emerged the outstanding orator in the Chamber on social questions. “What is lacking in the unions as you conceive them, unions of employers or of workingmen, isolated and separated from one another, is precisely what is the great want, the great social necessity of our time, and what existed at the basis of the old guild institutions, namely, personal contact, conciliation of interests, appeasement, which cannot be had except by the reconstruction of the industrial family.” In prophetic fashion De Mun went on to tell what would happen if workers joined their own unions and employers formed their own associations. Capital and labor would be organizing for war, and “in this impious war, everybody will suffer: the workers first, because they are weaker; the masters, also, who little by little will be ruined; and finally the entire country.”

(198)

Therefore, considering the so-called Fourth Industrial Revolution we are living in the midst of, Catholics ought to learn from the wisdom and piety of De Mun and the others portrayed in this book to reconstruct the Catholic family and the Catholic community. From these seeds, can the great tree of a new and better society which not only acknowledges, but sincerely dedicates itself to the cause of Christ the King, grow and flourish. Of the thirteen persons described in this work, I knew the names of seven; but even of these seven, I did not know much in comparison to what this excellent work had to offer. Thus, I recommend the reading of this book to all for its deeply educational and inspirational value. Priests should read this work, so that they may not only obtain a better grasp on history, but also that these salutary biographies may assist them in forming new lay leaders. Laymen should read it, so that the leaders among them may be guided by examples of sincere Catholic leadership, and the natural followers among them may know what traits to look for in a true leader.

As the learned Joseph de Maistre—who is given a superb chapter in this work—once wrote:

I see no reason why men of the world, who from inclination have applied themselves to serious studies, should not number themselves among the defenders of the most holy of causes.

(219)

-

Neill, Thomas P. They Lived the Faith: Great Lay Leaders of Modern Times. Mediatrix Press. 2020.

-

The most shameful example of this phenomenon in recent memory is the pathetic appraisal engaged in by some Catholics over the late Queen Elizabeth II of Britain. Not only was she the Governess of the Anglican church—thus a leading figure of a false religion—but also was a terrible leader to her people, for she and the not-so merry House of Windsor have sat in their castles and have only abetted the ongoing demographic replacement of their country.

-

The decade in which this work was originally published.