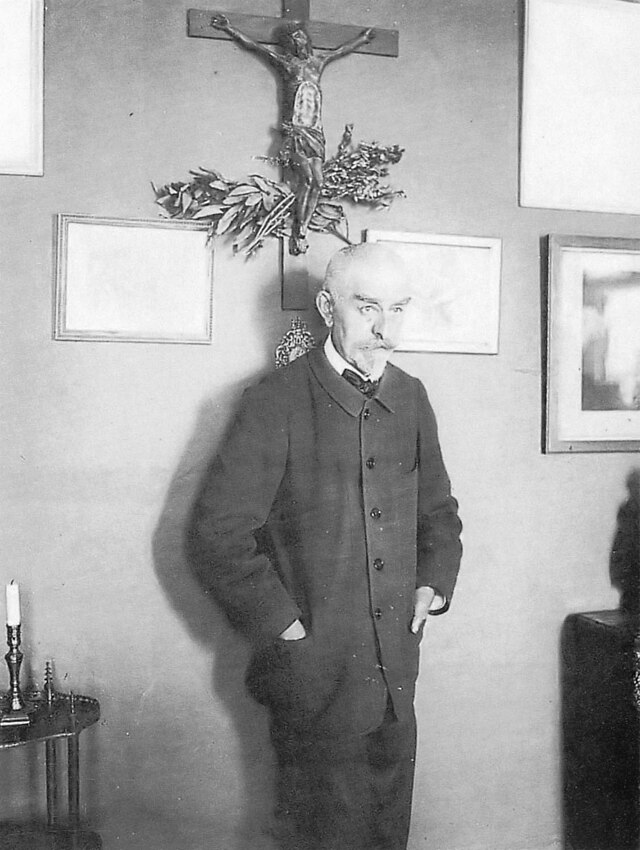

Joris-Karl Huysmans, photographed by Dornac

Available from Amazon

Book Length: 592 pages

Sadly a mostly forgotten man in the Anglophone world, there is much about the great Dutch-French author Jori-Karl Huysmans that is worthy of our attention. For not only was he a skilled painter of words, as he also lived a life of artistic intensity—an intensity that helped him return to God. In his Durtal trilogy, he left us with Catholic fiction that undoubtedly ranks with the Divine Comedy; like Dante, in these works Huysmans provides a portrait of his times that does not drown out the spiritual content, but elevates it, rendering the trilogy capable of speaking to all ages. It is thus unfortunate that he seems only to be remembered for his pre-conversion novels, as it was in his Catholic trilogy that he reached his spiritual and artistic pinnacle. But while one will gain much from investigating Huysmans’ literary corpus, if one wishes to grasp their depth, one must seek after the character of Huysmans himself. And many decades ago, Robert Baldick provided the world with his biography The Life of J.-K. Huysmans, an invaluable resource to all who wish to know the real Huysmans.

Something that will become evident to any reader of this biography is that the problem of suffering was simply unavoidable for Huysmans. Though it may indeed be truthfully said that this is a problem that we must all grapple with at some point or another, suffering was so prevalent in Huysmans’ life that one must conclude that unlike most people, it was not something he could drown out through worldly diversions. For as Baldick writes:1

(297-298)

Huysmans would appear to have been born to suffering, both physical and spiritual. A martyr to innumerable ills, of which neurasthenia was perhaps the one which affected him most deeply, he was abnormally sensitive not only to physical pain but to the petty miseries of life; he found his personal relationships unsatisfying and the company of his fellow men frequently intolerable; and his mind was perpetually torn by fears, doubts, and scruples.

But it was not merely the presence of suffering in his life that is so notable; it is what he did with that suffering. Eventually, he came to realize that he could transform the seeming meaningless of his physical and spiritual pains into something noble through his writing. He also came to believe in the doctrine of mystical substitution, a subject which would recur as a point of interest throughout his post-conversion works and in his own letters. As a result of his willingness to accept the ignominy of the Cross he became a great penitent and a profound writer, guaranteeing his literary immortality.

Before that could happen, however, he had to abandon his love of Schopenhauer and return back to the bosom of the Church, which did not happen until his forties. Rightly he could say with St. Augustine: “Too late have I loved Thee, O Thou Beauty of ancient days, yet ever new!”2 And like that great saint, he would write his own literary confession in his novel En Route. For despite the novel’s thematic function as a work of fiction, it contained a great sum of autobiographical details pulled from Huysmans’ own conversion.

The frankness of his account was not intended to scandalize, but to instead pull off the delightful mask behind sin—as Dante famously did in Inferno—and illustrate to all the bliss that comes with the true spiritual life. As the following selection from a letter he wrote reveals, Huysmans firmly believed that this was an artistic necessity in order to convert the sick souls of his age:

(315)

I agree that some pages could have been suppressed — but if you consider the non-Catholic public at which I was aiming, I risked compromising everything by not being frank and outspoken. For after all, what is a Catholic? — a man who is either healthy or cured. The others, sick men. To cure them, would you give them all the same medicine? Surely not. You would admit, would you not, that the very ill, such as I was myself — and they are many— cannot be cured with soothing drugs: they have to be given an emetic and forced to bring up their past lives. Well, for them my book has been something of the kind — a spiritual vomitory! It is powerful medicine — but if it cures only one sick man (and this it has done) what doctor of the soul could condemn it? The book has effected conversions of which I have certain knowledge, and others are ready. This phenomenon astonishes many of the priests who witness it, but they testify to its reality. As for the patients, they must have been seriously ill to have taken that horse-medicine! And isn’t the knowledge that they are cured the finest reward God could give me for my efforts?

Indeed, his assertion that En Route “effected conversions” was no boast. Baldick accounts for a number of these, with perhaps the most striking story being the following, as told in another of Huysmans’ letters:

(465)

I’m in correspondence with one of the ladies-in-waiting at the Court of Saxony. This woman has been conscious of a vocation for the Cistercian life ever since her childhood—and has deliberately rejected it. Once, when she was seriously ill, she was suddenly cured after swearing that she would take the veil, and a saintly old priest, who offered his life to God in exchange for hers, died in her place . . .And she broke her word. She then decided to marry — and on the evening of the wedding her fiancé suddenly died. After that she lived a wearisome social life at court, until chance put a copy of En Route into her hands. It seared her soul like a red-hot iron. She wrote to me, hoping that I wouldn’t reply. I replied. And now she is going to take the plunge and is looking for a suitable Cistercian convent . . .

Thus it can be truly stated that Huysmans heeded well the words of St. James the Lesser: “He must know that he who causeth a sinner to be converted from the error of his way, shall save his soul from death, and shall cover a multitude of sins” (James 5:20). For when one reads Baldick’s recounting of the author’s saintly death, we find a man who refused the comfort of morphia injections on his deathbed to better make reparation for his sins; a man entirely different from the dissolute seeker of prostitutes one reads of in the beginning of this Life. Huysmans not only crossed back over to the safe bank of the Tiber; he was adamant to build a bridge through his Durtal trilogy to all those on the other side, and eager to aid the “patients” of En Route beyond the initial imbibing of his striking words. No doubt all this effort won him immense favor in the eyes of Providence—and neither should it surprise the serious Catholic that Huysmans was a true devotee of Our Lady, something which is thankfully given due attention by Baldick.

Huysmans is needed now more than ever before. This great author not only became a representative of that European high culture which is so monstrously attacked, but also a representative of the authentic Catholic spirit against the bourgeois bastardization of the Faith that was well underway in his time. And he also presents a clear example of the truth that God has not made us for Hell, no matter how degenerate—for by the same artistic talent that Huysmans used to scandalize the public in his youth, he went on the edify the whole country in his later years.

This Life then is recommended to the scholarly lover of literature. Baldick’s work is a well-written and thorough chronicle which contains thoughtful inclusions of selections from his letters and works, and is respectful of the Church that Huysmans loved so much.