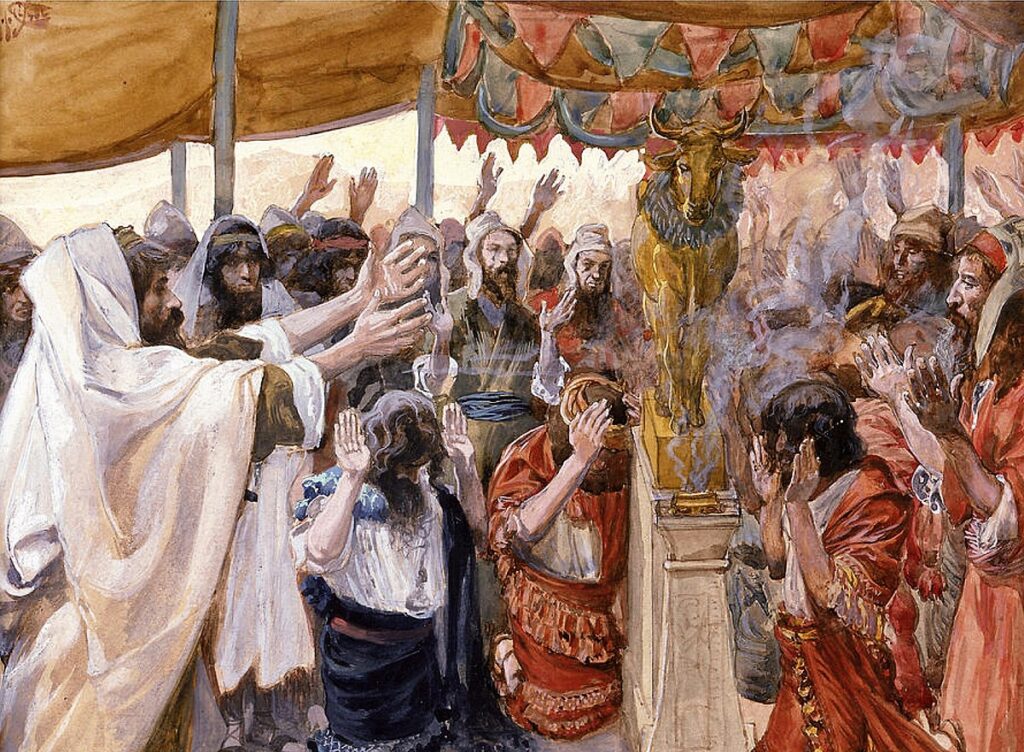

The Golden Calf by James Tissot

Available from Abebooks, Thriftbooks, Amazon, and from the publisher, Bloomsbury.

Book Length: 305 pages

Their ideas have polluted the minds of many, yet their authors are relatively unknown. In this book, the late English Conservative philosopher and writer Sir Roger Scruton has left to the public a highly insightful guide to the beliefs and personalities of the New Left. This faction, contrary to the opinions of some, is still left-wing in the sense of their application of the same principles which guided what can comparatively be termed the Old Left. The novelty, then, of the New Left consists in their taking those principles to extremes previously unknown.

On this genealogy of ideas, Scruton comments:1

The left-wing position was already clearly defined at the time when the distinction between left and right was invented. Leftists believe, with the Jacobins of the French Revolution, that the goods of this world are unjustly distributed, and that the fault lies not in human nature but in usurpations practised by a dominant class.

(3)

Thus, there is a direct line of thought that runs all the way from Rousseau to Marx, from Gramsci to Žižek. And in this book lies a great deal of documentation on that point, though Scruton’s erroneous enchantment with the so-called “Enlightenment” makes him miss what will be evident to Catholic readers; this “Enlightenment” was truly an intellectual darkening, for in removing philosophy from the truth of Divine Revelation, what inevitably followed was equivalent to the effects of the Protestant Revolution.2 As with that revolution, the cost of casting aside the Holy Faith resulted in chaos, not in a reformation of thought. Evil was again called good, and good evil; unreason was called reason, and piety was called superstition. The division in the intellectual realm reached such a point that even Rousseau himself wrote of his contemporary philosophers that “If you count their voices, each speaks for himself.” To this, Joseph de Maistre wisely observed, “Behold, all at once, the condemnation of philosophy and the charter of philosophy inflicted on Rousseau by Rousseau himself.”3 But such disorder was not content—for it never is—to remain in the realm of books and debates. For in a manner much akin to the Thirty Years War, this destructive trend of unbelief eventually culminated in the terrors of the French Revolution.

The germ of Liberalism survived the aftermath of the Revolution and the subsequent Napoleonic Wars, eventually spawning the twin plagues of Socialism and Communism in the 1840s. Going further ahead into history in the twentieth century, the theories of Marx were adapted in various ways by his disciples to accommodate the failures of the classical Marxist worldview. Such revisions of their false prophet’s original ideas are extensively covered in the text by Scruton, for several of the examined thinkers engaged in this practice, while the others simply built on the edifice which the revisionists had made. Where theory did not suit reality, the reality was made to conform to the theory.

Scruton undertook an incredibly impressive labor in sifting through the vast volumes of a numerous selection of academia’s golden calves, finding therein a great sum of nonsense, lies, and outright imbecility. Castigating the intellectual dishonesty of these false prophets, he writes:

The intellectual labour of the New Left has been not to prove the Marxist theory but to describe the world as though it were true, so that every existing fact seems to resonate with the voice of the oppressed.

(228)

And furthermore:

The language of the New Left is a language of accusation and defiance.

(Ibid)

Are these points not self-evident when calling to mind the everyday phrases and buzzwords one hears from the intelligentsia and their avid disciples?

Consider, for instance, the twisting of the word “patriarchy” (which beforehand had only a neutral or positive term) into a pejorative against fatherhood, whether the father in question governs a spiritual or biological family. The cases of negligent or even abusive fathers are used by such persons as being symptomatic of the “patriarchy”; yet the traditional order they condemn under that term held such examples not as exemplars, but as reprobates. Such men were not formed in line with the principles of the old society, they were aberrations. However, such a disconnect does not prohibit these anarchic souls from defaming the characteristics of good fathers, for they with paranoid fervor see something tyrannical in even the most benign and virtuous.

Of course, the arguments made by the disciples of the New Left ideologues are really rooted in emotion, not in reason. The ideologues themselves, however, root their ideas in a cold, confusing, and practically impervious logic—this is no accident, as Scruton notes:

To achieve this new kind of truth it is important to avoid refutation, but not, as science avoids it, by courting and surviving counter-arguments. Refutation must be evaded, so that the truth within the dogma can be protected from the malice within real things.

(160)

Thus unlike Holy Mother Church, who proclaims her teachings in a language accessible to all, the teachings of the New Left are communicated through a language of negation and evasion. Indicated by this difference is that while on one hand the teachings of the Church build up man and civilization into conformity with the positive revelation of Jesus Christ, on the other the teachings of the New Left are subversive; they undermine and ultimately destroy both man and civilization.

Understandably, the author provides more coverage to certain thinkers than others. For example, Jacques Derrida, the founder of the Deconstructionist school of thought, is given about two pages or less. Juxtaposing this, Michel Foucault, the progenitor of “Queer Theory”, and Jean-Paul Sartre, the founder of “Existentialism” are practically granted a whole chapter—though like Derrida, both men were leading figures of the French New Left.

Further along this subject, there is an unfortunate oversight the author made in his treatment of the French New Left specifically, this being their involvement in the infamous petitions in their country against the age of consent.4 Such a revelation would not only have further discredited the moral character of the French intellectuals mentioned in this book, but also the others involved in that abominable movement. It would have also been intriguing for Scruton to engage in a more in-depth manner with the feminism of Simone de Beauvoir, and to explore Foucault’s role in “Queer Theory” and his magisterial influence on thinkers of that school. Despite these shortcomings and others, such as his ignorant ramblings about what is often termed the “horseshoe theory”, this book still retains its worth as a superb resource. Where Scruton gets things right, he delivers insight both highly memorable and valuable.

The author’s biggest triumph in this work, in my view, is the connection he makes between Gnosticism and the worldview of the New Left. With consistent eloquence, he argues that the New Left, despite all the claims made about the originality of their ideas, have knowingly or unknowingly repackaged the oldest Christian heresy. The paramount excerpt, which is well worth reading in full, has Scruton contrast the hopelessness of Sartre to the brilliance of St. Augustine:

What, it might be asked, is the true source of Sartre’s revulsion towards his incarnate existence—a revulsion exhibited now in a sense of obscenity, now in the post coitum triste of a desire that is nauseated by its own consummation? What is this feeling that focuses so specifically, and yet also erupts in Roquetin’s5 dismissal of the ‘bourgeois’ normality, and in a metaphysical nausea that embraces the whole of creation?

It seems to me that St. Augustine presented a better answer to that question than the one suggested by Sartre. For Augustine it is the sentiment of original sin that is the cause of our disgust at the world. We are ashamed at our incarnation whenever brought directly face to face with it, and we feel our inner freedom as ‘defiled’ by its fleshly prison. We see ourselves as exiles in the world, constantly overcome by the stench of mortality.

…

If we put together the more powerful of Sartre’s observations – and those that play the most important role in his metaphysic of freedom – we are clearly not far from the Augustinian spirit: the spirit of the Christian anchorite raging against the pleasures of this world, and yet uncertain that he has really renounced them. And the chilling awareness of defilement that turns the anchorite to God turns Sartre, who sees no God, to his lonely inner sanctum, where the self is enshrined amid the cluttered icons of its own futile make-believe.

(82-83)

In this sense, the aforementioned Gnosticism of the New Left becomes apparent; they consider the material world evil—hence their invectives against “inequality” even in the most expected of places—and wish to redefine it according to the perceptions of their souls, which according to them have the real grasp of truth. Hence their tacit endorsement of the new order of things, in which the beautiful are replaced by the ugly and the high-born are cast out in favor of the lowest common denominator. They bastardize language in order to give themselves an aurora of mysticism, to ensure that only the committed member of the academic caste can really ever understand them, while the average person is left confused by their winding and nonsensical words. These things are ingredients not for liberation, but for tyranny.

Therefore, in spite of the author’s shortcomings, this Anglican managed to capture and dissect the most immediately destructive ideas of our time, and for that this work ought to be praised and read—albeit with discernment. This is not a read for everyone, for as can be expected from a work of this sort, it delves extensively into philosophy. However, for those Catholics and others who are philosophically minded, this is surely a book worth reading.

-

Scruton, Roger. Fools, Frauds and Firebrands: Thinkers of the New Left. Bloomsbury. 2019.

- For more information, see for reference this video: “Crisis Series #3 with Fr. Wiseman: Origins – Descartes & Kant.” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gYpCg2_n3js&t=6s.

-

Maistre, Joseph de. Study on Sovereignty. Translated by Edward Maxwell III. Maistre: Major Works, Vol. I. Imperium Press. 2021. p. 221.

- “French petitions against age of consent laws.” Wikipedia.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/French_petitions_against_age_of_consent_laws.

- The protagonist of Sartre’s 1938 novel La Nausée.