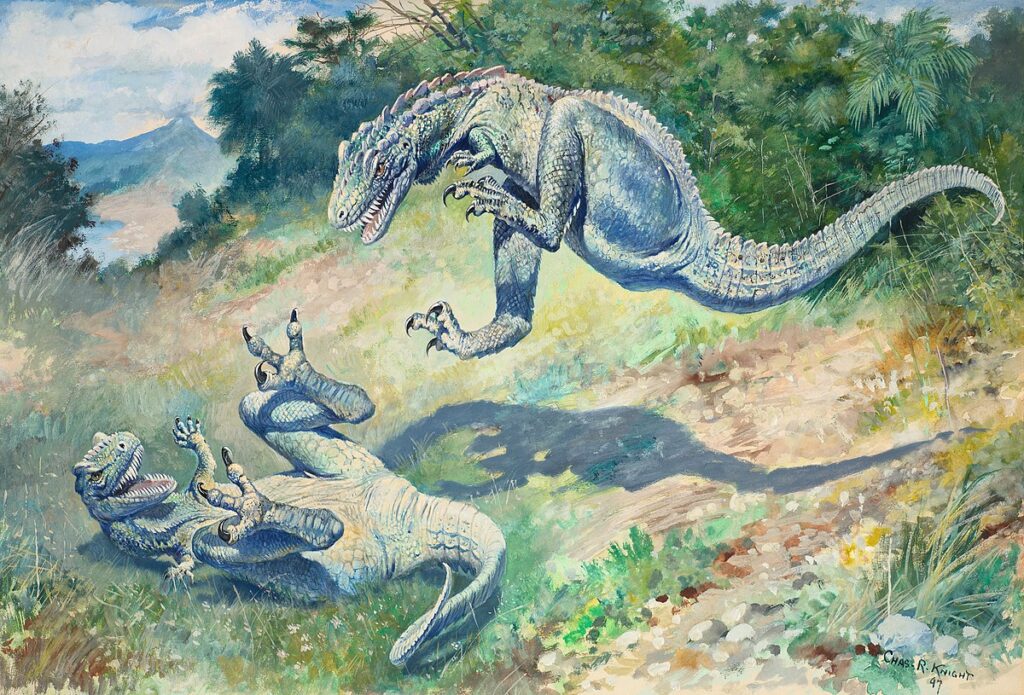

Leaping Laelaps by Charles R. Knight

“You have heard that it hath been said, An eye for an eye, and a tooth for a tooth. But I say to you not to resist evil: but if one strike thee on thy right cheek, turn to him also the other: And if a man will contend with thee in judgment, and take away thy coat, let go thy cloak also unto him.”

– Matthew 5:38-40

In light of the common charge hurled against Creationists that Creationism itself is a laughable pseudoscience because some scientists who have been or are involved in this movement are “unprofessional”, “quacks”, and “con-men”, it is instructive to note that the clean, honest image of mainstream science so smugly advertised by Evolutionists is blatantly false. The field of paleontology alone presents more than a few cases which illustrate that establishment scientists are just as capable—if not even more so—of producing hoaxes and engaging in scientific malpractice. One such case is that of the so-called “Bone Wars” of the late nineteenth century.

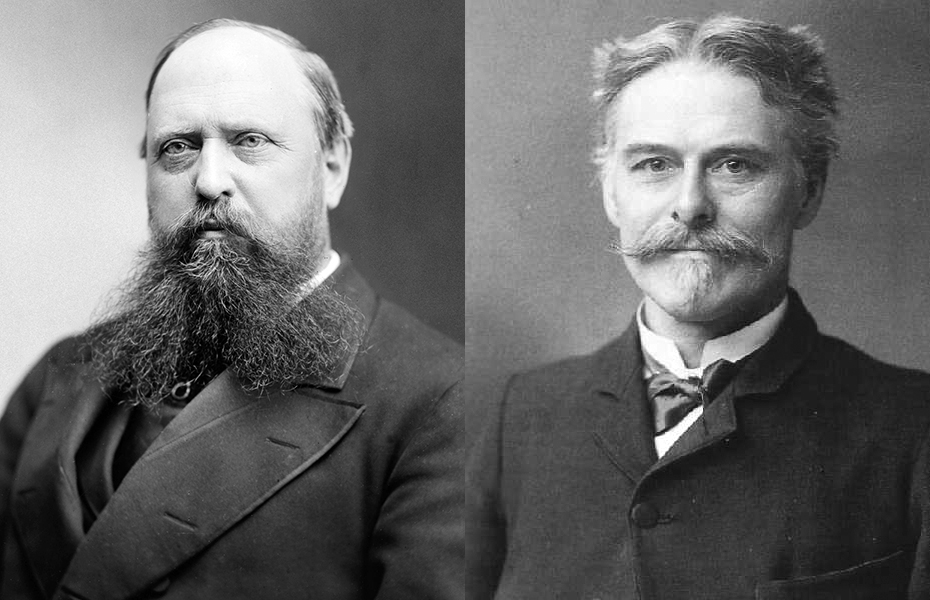

Othniel Charles Marsh (left) and Edward Drinker Cope (right)

The story of these “wars” were dominated by the figures of Othniel Charles Marsh (1831-1899) and Edward Drinker Cope (1840-1897), two men who, despite initially forming a cordial relationship between one another, descended into a bitter rivalry that would continue for the rest of their lives. As an article from PBS American Experience states:1

In 1863, to avoid Cope being drafted into the Civil War, Cope’s father sent his son to Germany to study natural history. There he met graduate student O.C. Marsh.

Upon returning to the U.S. in 1864, Cope and Marsh maintained their amicable relationship. Cope named an amphibian fossil Ptyonius marshii, after Marsh in 1867, and, in return, the next year Marsh named “a new and gigantic serpent from the Tertiary of New Jersey” Mosasaurus copeanus.

Marsh’s reciprocal gesture, however, was far more complicated. In 1868, in an act of friendship, Cope had shown Marsh around a fossil quarry in Haddonfield, New Jersey. Behind Cope’s back, however, Marsh made an agreement with the quarry owner to have any new fossils sent directly to him at Yale. Cope would later describe the act as the beginning of the end of their friendship.

“O.C. Marsh and E.D. Cope: A Rivalry”

Another incident that only added further fuel to the rift between the paleontologists was Marsh’s correction of a mistake made in Cope’s reconstruction of an Elasmosaurus specimen upon his visit to the display at the Academy of Natural Sciences in 1868. Cope had placed the skull of the creature at the end of the tail; errors like this may seem evidently foolish from a modern context, but considering that paleontology was still a young science at the time, it is quite understandable. This fumble irritated Cope to such a degree that he “quickly published a correction, and even tried to purchase all known copies of the American Philosophical Society journal with the error” in order to cover his reputation. Marsh himself stated that this error became the catalyst of their rivalry, as he would later reflect that “his wounded vanity received a shock from which it has never recovered, and he has since been my bitter enemy.” 2

This bit of commentary is quite ironic, as Marsh went on to make a particularly embarrassing mistake himself amid the fast-paced competition of the Bone Wars, which kicked off in 1877, nearly a decade later, as recounted by PBS WTTW:3

The Bone Wars started in earnest in 1877 when a geologist named Arthur Lakes discovered massive dinosaur bones near Morrison, Colorado. He tried to alert Marsh to his findings, but Marsh was slow to respond, because at the time he was more interested in mammal fossils than dinosaurs…So Lakes instead sent some specimens to Cope. That got Marsh’s attention, and Marsh hired Lakes and sent more of his crew to Colorado to begin the mad dash for dinosaur bones.

Over the next decade and a half, a gold-rush-type of mania consumed Cope and Marsh, who constantly tried to outdo one another. Their tactics became shady. Marsh supposedly bribed people to work for him instead of Cope, hired spies to snag intel on the findings of his nemesis, and even wrote covert letters and telegrams giving Cope the code name, “B. Jones.”

…

When Marsh discovered a long-necked dinosaur in 1877, he named it Apatosaurus. But the incomplete specimen was missing its skull, so Marsh guessed that a skull found elsewhere belonged with the Apatosaurus. Unfortunately, it was actually the skull of a Camarasaurus. When he examined another long-necked fossil a couple of years later, he named that one Brontosaurus. But it was actually just an Apatosaurus, this time with the correct skull.

“The Two Paleontologists Who Had a Bone to Pick with Each Other”

Marsh’s misnaming of sauropod skulls went on to have a much more long-lasting consequences than Cope’s Elasmosaurus blunder. This very mistake was the reason why, for well over a hundred years afterwards, the names Brontosaurus and Apatosaurus were used to refer to the same animal, something which happens even in the present day. This confusion happened and circulated despite the efforts of subsequent paleontologists to correct this error, which illustrates just how much of a (though in this case quite benign) cultural impact a scientific mistake can have. Brontosaurus, intriguingly enough, was also not considered as its own separate genus until 2015.4

As the article from PBS American Experience relates, the Bone Wars only escalated after Marsh’s effort to rush his discovery:

Cope competed by rushing to publish his findings in academic journals, a practice paleontologist Bob Bakker calls “taxonomic carpet-bombing”. Going further, in an effort to ensure his work got recognized, Cope purchased The American Naturalist journal in 1877. Between 1879 and 1880, Cope published 76 academic papers, a small percentage of the 1,400 articles he would write over the course of his lifetime, making him one of the most prolific authors in American scientific history. In just a few years, the number of known dinosaur species jumped from a small handful to more than a hundred.

Marsh was determined to put his rival out of business. In 1882, he used his superior connections and political skills in Washington, D.C. to become chief paleontologist of the newly-formed U.S. Geological Survey. This gave Marsh access to an immense amount of institutional support; not only did he have access to federal funds, but he gained a significant amount of political power. He set about isolating Cope, cutting him off from the government funding which both men had relied on over the years, especially for the preparation of expensive, illustrated volumes reporting on their fossil discoveries. A desperate Cope attempted to make up for the loss in a silver mining venture in New Mexico. Instead, he lost everything.

“O.C. Marsh and E.D. Cope: A Rivalry”

Thus Cope hijacked scientific literature in his attempt to outmatch Marsh, and Marsh retaliated by abusing his newfound government position to limit his rival’s ability to compete against him. Impartiality, one of the great virtues ascribed to the scientific profession, had been ruthlessly violated by both men. However, the causalities of the Bone Wars reportedly even extended to the bones themselves, as the PBS WTTW article relates:

The two men found so many bones that their respective institutions didn’t have a place to store them all. There are even some accounts that claim that Cope and Marsh were so competitive, they stole from one another and destroyed any leftover bones from a dig site just to prevent them from falling into the “wrong hands.”

“The Two Paleontologists Who Had a Bone to Pick with Each Other”

Despite these unfortunate consequences of their petty war, the worse was yet to come. There would be no reconciliation between Marsh and Cope; both men pursued the “Bone Wars” to their professional and financial ruination:

By 1890, separated from his wife and child, Cope was living alone in a small Philadelphia apartment. His fossil collection was all he had left. Marsh then made a fatal mistake. He attempted to take Cope’s fossils, claiming they had been collected with federal money and thus belonged to the government. Cope fought back, producing evidence that he had paid for almost all of his collecting out of his own pocket. Then, he set out to destroy Marsh.

For years, Cope had been collecting information—records of nefarious, underhanded dealings and accusations of scientific impropriety—to use against Marsh. He turned them over to a freelance journalist at The New York Herald, an eager purveyor of scandals. The headline, “SCIENTISTS WAGE BITTER WARFARE,” set off a firestorm. The public battle lasted for two weeks, as the professors fired accusations at each other. Marsh and his allies in the U.S. Geological Survey were publicly accused of corruption, incompetence and misuse of government funds. Congress investigated and eventually slashed funding for the Survey, eliminating the department of paleontology along with Marsh’s position, power, and most of his income. As a final indignity, the Smithsonian demanded that Marsh turn over a large part of his own fossil collection, some of which had, in fact, been collected with government funds.

The paleontologists’ flare for public slander had damaged both of their reputations. Cope was unable to find a bidder who could afford his entire fossil collection, which he had spent over 20 years developing. Finally, a fellow at the American Museum of Natural History bid $32,000 for part of the collection. In 1897, Cope became ill and died at 56.

In 1899, at the age of 67, Marsh died of pneumonia with just $186 in his bank account. Over 80 tons of Marsh’s personal collection of fossils was acquired by the Smithsonian, but Marsh left the bulk of his collection to the Peabody Museum of Natural History at Yale.

“O.C. Marsh and E.D. Cope: A Rivalry”

The kinds of sinful, absurd, and destructive acts committed by both men during these “wars” are so unbecoming of any scientist that they approach the outright juvenile. Undoubtedly, these examples would readily be marshaled by Evolutionists against Creationism if Marsh and Cope were Creationists. Yet, when it is men who agree with their ideas who dishonor the scientific profession, they calmly disassociate themselves from such characters and would point out that an attempt to discredit their own ideas on the basis of this immoral conduct would be an ad hominem fallacy. Of course, such charity is never afforded to Creationists.

As to the legacy of the “Bone Wars”, the PBS American Experience article concludes with this sentence:

Cope left behind 13,000 specimens, and Marsh’s comparable collection proved to be “the best support of the theory of evolution,” according to a personal letter from Charles Darwin himself.

(Ibid)

This is quite an ironic statement, in two ways. Firstly, the dubious manner in which the bones were found and the intensely vicious competition for them between Cope and Marsh appears as a faithful imitation of Darwin’s atheistic “survival of the fittest” concept. Secondly, the fossils themselves, far from supporting the theory of evolution, vindicate the views of Creationists once the fog of Darwinian interpretation is cleared from the mind. Such an exciting subject, however, will be given the coverage it deserves in a future post.

-

“O.C. Marsh and E.D. Cope: A Rivalry.” American Experience. PBS. www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/dinosaur-rivalry/.

- Ibid.

- “The Two Paleontologists Who Had a Bone to Pick with Each Other.” PBS WTTW. interactive.wttw.com/prehistoric-road-trip/detours/the-two-paleontologists-who-had-a-bone-to-pick-with-each-other.

- “Brontosaurus.” Prehistoric Wildlife. www.prehistoric-wildlife.com/species/b/brontosaurus.html.