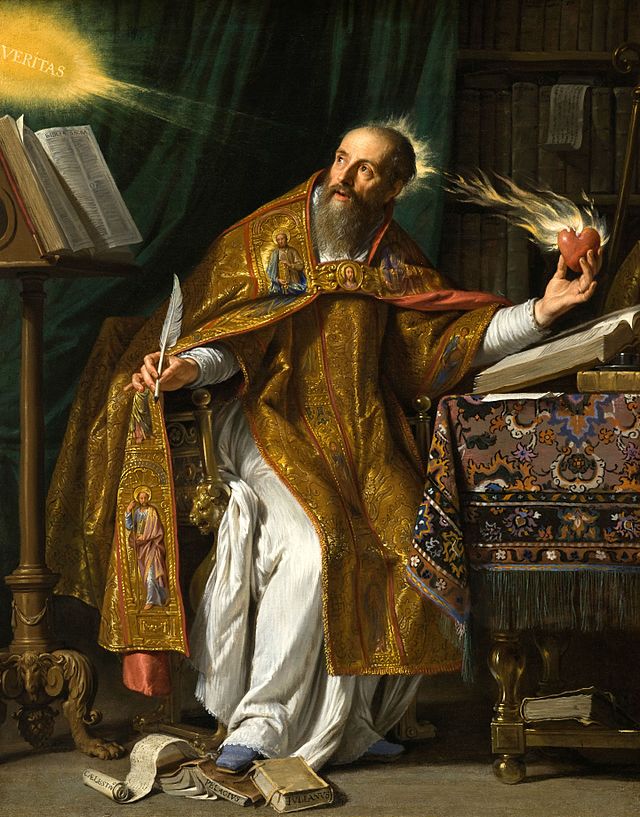

Saint Augustine by Philippe de Champaigne

Available from Abebooks, Biblio, and Amazon. You can also listen to this book for free on Archive.org and read it online at Georgetown.edu!

Book Length: 338 pages

In the history of literature, there are few books more renowned than St. Augustine’s Confessions. In the history of Christian literature, this is only doubly so. The deep insight which this great saint gives us concerning the events of his life, his most personal thoughts, and on theological truth have influenced the lives of many Catholics from generation to generation. Though it may be true that most writings evade simple paraphrase, that is especially true of this one. Entire books could be written in an attempt to catalog and comment upon each and every edifying moment within this magnificent autobiography. However, even volumes of such explanatory texts would miss essential points, for there are simply too many of them to be covered. Therefore, as this review will only delve into small parts of this work and expound upon them, I caution my dear reader that my analysis stands as a mere glimpse of a glimpse into that radiant window which is the Confessions.

St. Augustine’s life was filled with suffering. The greatest of these, as he tells us, was his restlessness which resulted in a life lived outside of God’s friendship. However, his life was filled with joy; he was transformed into a tormented searcher of truth into a valiant defender of He who is truth—”Every one that is of the truth, heareth my voice” (John 18:37).

His meditation, therefore, on how suffering precedes Christian joy can be seen as a reflection of his own life. The good saint begins first with considering the conversion of the great Roman scholar Victorinus, glorifying the divine mercy in terms which directly allude to Biblical parables:1

Good God! what takes place in man, that he should more rejoice at the salvation of a soul despaired of, and freed from greater peril, than if there had always been hope of him, or the danger had been less? For so Thou also, merciful Father, dost more rejoice over one penitent than over ninety-nine just persons that need no repentance. And with much joyfulness do we hear, so often as we hear with joy the sheep which had strayed is brought back upon the shepherd’s shoulder, and the groat is restored to Thy treasury, the neighbors rejoicing with the woman who found it; and the joy of the solemn service of Thy house forceth to tears, when in Thy house it is read of Thy younger son, that he was dead and liveth again; had been lost, and is found. For Thou rejoiceth in us, and in Thy holy angels, holy through holy charity.

(149)

St. Augustine then applies this spiritual truth to examples from everyday experience, illustrating how even in worldly matters this same pattern of great joy being preceded by great suffering occurs:

A friend is sick, and his pulse threatens danger; all who long for his recovery are sick in mind with him. He is restored, though as yet he walks not with his former strength; yet there is such joy, as was not, when before he walked sound and strong. Yea, the very pleasures of human life men acquire by difficulties, not those only which fall upon us unlooked for, and against our wills, but even by self-chosen, and pleasure-seeking trouble. Eating and drinking have no pleasure, unless there precede the pinching of hunger and thirst.

(150)

Thus he concludes, “Every where the greater joy is ushered in by the greater pain” (Ibid). Indeed, if we ask God to enlighten us—if nothing immediate comes to mind—we can find many examples from our lives which testify to this truth. What folly is it, then, that the world considers the elimination of every suffering, from the most minor of discomforts to the horrors of war, as not only feasible, but desirable! Souls may well try to flee suffering, but apart from embracing one’s cross, such attempts always end in futility; no, even worse than this—the creation of even greater sufferings. The rampant loneliness among the youth of our age will not be solved by the introduction of new social programs or artificial intelligence companions, but by the “holy charity” St. Augustine writes of. The holy charity of God kindles the flame of charity in His followers and in His saints; we are called to be the light of the world (Matthew 5:14). We must especially beg Heaven to receive the everlasting virtue2 in our time, for as Christ said, “And because iniquity hath abounded, the charity of many shall grow cold” (Matthew 24:12).

In connection with charity comes friendship, a subject which the saintly author also discusses in this work. After lamenting the falseness which permeated his friendships in youth, he explains how friendship among men is perfected by friendship with God:

Blessed whoso loveth Thee, and his friend in Thee, and his enemy for Thee. For he alone loses none dear to him, to whom all are dear in Him who cannot be lost. And who is this but our God, the God that made heaven and earth, and filleth them, because by filling them He created them? Thee none loseth, but who leaveth. And who leaveth Thee, whither goeth or whither teeth he, but from Thee well-pleased, to Thee displeased? For where doth he not find Thy law in his own punishment? And Thy law is truth, and truth Thou.

(62)

How salutary would it be for us to view to the loss of our friends in this light! And I do not necessarily refer to death in mentioning “loss”; for when our friends depart from any interaction with us (or even from the same vicinity as ourselves) do we not sense a real, though lesser, loss? But in the life of grace, we never do truly lose our friends. They are with us always because Our Heavenly Father watches over our friends and ourselves, even if they are sinners or infidels, as it is written that He “maketh his sun to rise upon the good, and bad, and raineth upon the just and the unjust” (Matthew 5:45).

Our prayers for our friends who are not friends of God joins us to the intentions of Our Heavenly Father, who desires that all men be saved and come to the knowledge of the truth (1 Timothy 2:4). and we show the greatest possible charity in this towards them. We are also joined to our friends in such acts, for if they convert or repent they will be on the path to fulfilling the end of man, which is to obtain the vision of God.

Yet, we are all the more joined together with our friends if they are also in the life of grace, because if this condition is met, we share a place within the Mystical Body of Christ with them. Thus even if we suffer the loss of being separated by death from these friends, we are never truly separated from them; we can expect to meet them in eternity, and enjoy the company of God and His saints forever with them. But even in this valley of tears—thanks to the generosity of the Almighty—we can, drawing upon the well of grace, offer the spiritual riches of prayers and good works for them, and they too can do the same for us. As virtuous friends are bettered by witnessing the good example of the other, even more so are we bettered by this liberality. O glorious mystery!

Now that St. Augustine’s coverage of the goodness of charity has been related to the extent that it can in this brief summary, his description of evil can be adequately touched upon. Though this passage will likely be familiar to my readers as it is among the many great theological passages of this work, I will quote it here and expound upon it:

And I enquired what iniquity was, and found it to be no substance, but the perversion of the will, turned aside from Thee, O God, the Supreme, towards these lower things, and casting out its bowels, and puffed up outwardly.

(137)

Evil has no being of its own—therefore it can only corrupt, it cannot build. Having been fed the lies of the Manicheans, St. Augustine (as he tells us) was confused on the nature of evil for some time, given the odious falsehood which that sect and all the Gnostic sects before or since have propagated: this being that evil is a substance of its own being, having been created alongside good as a kind of equal. After asking to be enlightened, however, the good saint was given this light by He who is Light, who is Goodness; and this same light has been handed down from generation to generation through this book, even to our benighted time. And in this age, this truth must be better made known, for in our world the partisans of error have been successfully deceiving the masses since the 1960s (at least) that evil is not only acceptable, but that it is indeed equal to good. It is an outrageous falsehood that underlies so many others—wickedness is not equal to wisdom, and promiscuity is not equal to purity; they never will be. Evil is a deprivation, as it deprives us of virtue, without which we cannot be truly happy. Man was not created by the Devil, that liar and murderer from the beginning who cannot make anything. No—man was created by God to share in His love.

Without the love of God, then, man cannot be truly fulfilled. St. Augustine, considering his life before his conversion and the renunciation of his sinful ways that followed from that decision, writes in another renowned passage that:

Too late loved I Thee, O Thou Beauty of ancient days, yet ever

(221)

new! too late I loved Thee! And behold, Thou wert within, and I abroad,

and there I searched for Thee; deformed I, plunging amid those fair

forms which Thou hadst made. Thou wert with me, but I was not with

Thee. Things held me far from Thee, which, unless they were in Thee,

were not at all. Thou calledst, and shoutedst, and burstest my deafness.

Thou flashedst, shonest, and scatteredst my blindness. Thou breathedst

odours, and I drew in breath and panted for Thee. I tasted, and hunger

and thirst. Thou touchedst me, and I burned for Thy peace.

So many are “restless” today, as was St. Augustine. They know nothing of the “gift of God” (John 4:10) and little to nothing of His commandments and His promises. Ignorance is not bliss; it leads to doom. In comparing the vain wanderings of young St. Augustine to the hidden glory of St. Stanislaus Kostka, one can more easily understand the chasm that separates the joy and vitality of Christian life from the sterility and anxiety which underlies that of the infidel. The answer to our restlessness is the same as St. Augustine’s—a life lived in and for Jesus Christ, in the unity of the Holy Catholic Church He founded.

Let it be written here that conversion alone does not immediately resolve evil habits. A change of life, of action, is needed which is in concordance with the life of the “new man” (Ephesians 4:24). Even if one is fighting against venial sins, as the author was when writing this work, his words on the spiritual battle which follow from the aforementioned passage still apply: “because I am not full of Thee I am a burden to myself” (Ibid). He means this: because I am not full of God’s boundless purifying love, I am a burden to myself because I can sin and thereby damage my relationship with Him.

In closing, this book is recommended reading for all Catholics. This work has rightly earned its place among the other great spiritual classics, as over a thousand years has not been able to dilute the rich message it presents. St. Augustine has much to teach us about himself, but also about the magnanimity of God—and ourselves too; take up and read!

-

All quotations of this text are provided from:

St. Augustine. The Confessions of Saint Augustine. Translated by E.B. Pusey. Modern Library. 1949.

If one finds Pusey’s translation too antique, there are plenty of worthy alternative translations which are more intelligible to modern readers.

-

“And now there remain faith, hope, and charity, these three: but the greatest of these is charity.” (1 Corinthians 13:13)

“The order of charity must needs remain in heaven, as regards the love of God above all things. For this will be realized simply when man shall enjoy God perfectly.” (ST II-II, Q. 26, Art. 13, co.)